Search

The Strongest Link

The Strongest Link

For over two decades, the Link Fellowship at SMS has launched the careers of a diversity of marine scientists

By Michelle Z. Donahue

*The deadline to apply for the 2021 Link Fellowship is March 15. More information and application links can be found on the Graduate Fellowships section of the SMS website.

Starting a career is never easy, but science has a special hurdle for new researchers: finding funding and opportunities for independent research. At the Smithsonian Marine Station, the Link Fellowship has helped fill that gap.

Established in 1998, the Smithsonian Link Fellowship program is now in its 23rd year. Though only 12 weeks in duration, the residency has helped dozens of young scientists launch their careers. To a person, former Fellows interviewed for this article cite the independence the funding afforded them as a critical building block of their early careers.

Supported by the Link Foundation, which was founded by Marion and Edwin Link, the fellowship was developed under the leadership of SMS’s founding director, Dr. Mary Rice. Rice was also close friends with Edwin’s younger sister and longtime Vero Beach resident, Marilyn. Offered to graduate students to conduct research in the marine sciences at SMS, the Link Fellowship is one of several grants and fellowships funded by the Link Foundation. Edwin Link was a noted aviator and entrepreneur, inventing the “Link Trainer” flight simulator; later in life, he became interested in underwater exploration, and developed the Johnson-Sea-Link submersibles.

Dr. Valerie Paul, SMS head scientist, said that for the duration of her tenure at the station, fellows’ research has resulted in “significant progress” in their area of study, as well as diversifying the kinds of research that goes on at the station itself.

“The material published from these fellowships is really advancing marine science,” Paul said. “There have been such a diverse series of projects that run the gamut – from oceanography, to systematics, to ecology, you name it. It’s expanded our interests here at the station by having all these young and enthusiastic PhD and master’s students here doing research.”

Recipients of the fellowship have gone on to have unique staying power in marine science.

One of the program’s first fellows, Dr. Nancy Smith, said her 1998 fellowship enabled her to complete a two-year project on the life history of the marine snail Cerithidea scalariformis. That work went on to be published in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series. Soon after, in 2000, Smith joined the faculty of Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Florida, where she still teaches and conducts research today.

Smith has continued to collaborate with scientists and technicians at SMS and returns regularly to mosquito impoundments and mudflats around the Indian River Lagoon for her research.

“I genuinely believe the support I received from the Smithsonian Graduate Fellowship and the Link Fellowship were instrumental in helping me secure a faculty position,” Smith said. “During the fellowship, I was able to develop many collaborations with scientists at the Smithsonian and had hands-on research experiences with the natural systems in Florida.”

While mentorship by a senior scientist in the formative years of their careers is important for young scientists, the ability to flex their investigative muscles on their own gives a boost of confidence. Being handed a wide berth to pursue independent inquiry is an excellent opportunity for a graduate student, Paul said.

“The fellowship has a great impact on people’s careers,” Paul said. “Fellows are often able to get a chapter out for their PhD dissertations, and make significant progress in their research. That’s hard to do as a graduate student if you’re linked to a faculty member’s grant – it’s tough to be truly independent.”

Paul also noted that several former Link fellows have returned to SMS as postdocs, staff, or as affiliate researchers from other institutions. Two of SMS’s current scientists, Dr. Jennifer Sneed and Dr. Holly Sweat, were Link Fellowship recipients.

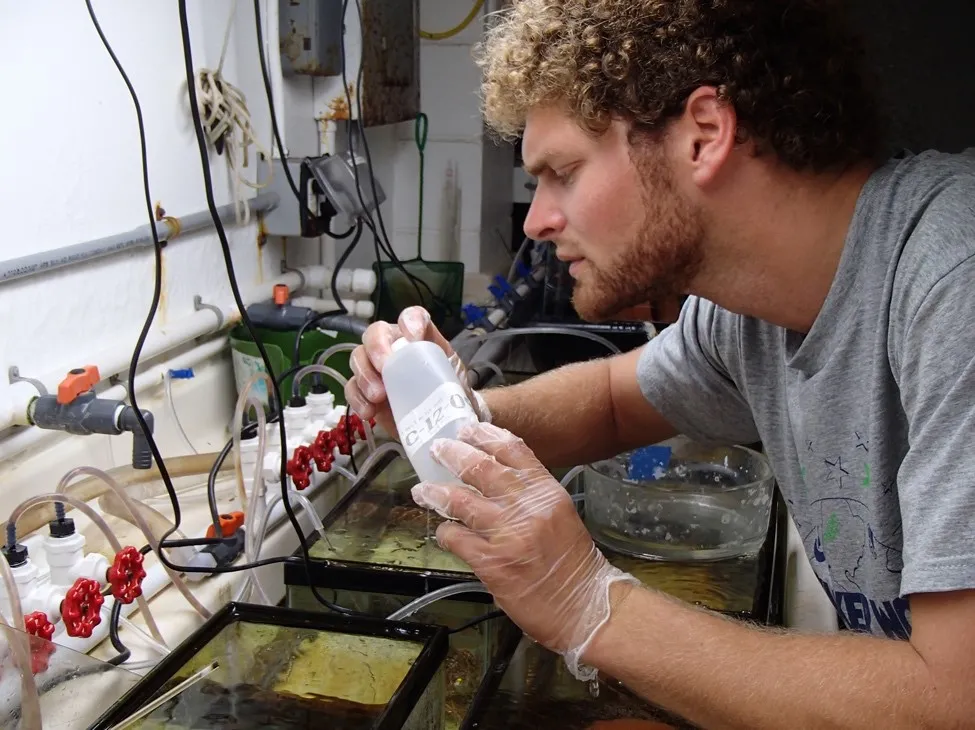

Sweat, who was a Link Fellow in 2012 as a master’s degree student, was working on a project investigating larval recruitment of invertebrate fouling organisms such as sponges and tunicates in ports. Sweat gathered data on communities that grew on artificial surfaces and natural surfaces in different ports—but the project also involved transplanting communities from one site to another to make differential observations. She said that without the fellowship, adding this dimension of research probably wouldn’t have made it into her doctoral dissertation.

In addition to clarifying her eventual postdoctoral research, Sweat said the fellowship was a much-needed shot of confidence for conducting research on her own. Having had Smith as her advisor as an undergraduate at Eckerd College, Sweat knew the profound impact the fellowship had on Smith’s career.

“The fellowship definitely laid the groundwork for inquiries I ended up doing later on,” Sweat said. “But also: it’s probably one of the earliest times in a graduate career where you’re planning and running an experiment, and you have only yourself to answer to, and nobody else. It’s long before you have to defend your dissertation, usually, so the fellowship is a really good primer for that process.”

Sneed came to SMS for the Link Fellowship in 2009. She was in the middle of her PhD work at Friedrich Schiller University in Jena, Germany, and with her advisor, Dr. Georg Poehnert, was researching microbes associated with certain species of tropical green macroalgae. After making short annual trips to the Florida Keys to study Dictyosphaeria ocellata, Poehnert suggested Sneed apply for the Link Fellowship.

“I would have had a much harder time getting fieldwork done, without being here in some capacity—and it certainly affected my career,” Sneed said. “I still work here!”

Dr. Philip Gravinese, who was a Link Fellow in 2004, researched the effects of changes in light intensity, pressure and the perception of gravity in larval stone crabs. Raising larvae at SMS and conducting darkroom experiments at Florida Tech, Gravinese said that the research he did was one of the first to describe larval swimming abilities of a fishery species worth over $30 million a year--and that was in decline from overfishing.

“The fellowship helped me get out of my comfort zone with my own colleagues and lab and advisor at the time,” Gravinese said. “I was able to learn some tools of the trade in another lab and get some experiences from other experts. Those lessons really stuck with me.”

He, too, said the fellowship helped strengthen his confidence as an early-career scientist. And, as a fellow at a Smithsonian lab—which in pre-Covid-19 days frequently would host visitors and tour groups—the fellowship gave him some of his earliest opportunities to interact with the public.

“It was some of my first experiences with talking about my research and why it was important, as outreach vignettes,” Gravinese said. “I definitely learned how to translate what I was doing from a nerdy, scientific way to more of a layperson way, to communicate why and how the work was important.”

Dr. Diana Chin, who was a Link Fellow at SMS in 2017, recently began a National Science Foundation postdoctoral research program at the University of Florida. She credits the strong start of her graduate career to her fellowship at SMS.

“Both because of the funding and because it was tied to the Smithsonian, I had a place to focus my research,” Chin said. “It helped me demonstrate to myself that I can manage a project, be in charge – be a scientist.”

--January 2021