Search

Finding New Homes

Finding New Homes

Scientists work to unravel the mystery of how fish and corals take up residence on reefs.

By Olivia Carmack

SMS Research and Communications Intern

Just like the beloved main character from the popular film Finding Nemo, young fish and coral larvae on reefs must keep swimming until they find their forever homes. The places they choose to settle down and build their futures may seem arbitrary to the untrained eye, but how and why they accomplish this task is far from random.

One secret? Chemical clues.

These clues, known as “chemical cues,” are signals that guide organisms, helping them choose homes, mates, foraging areas, and even how they interact with predators. Ants, for example, use chemical cues to communicate with one another about the location of a food source. As a worker ant leaves the nest, it releases a trail of pheromones, a chemical cue that lets the other ants know that there is a reliable source of food nearby.

Chemical cues are also an important form of communication in the marine environment. Like ants, juvenile fish and coral larvae also use chemical cues to navigate their environments. These chemically influenced interactions can define population demographics, community structure, and ecosystem processes, making it important for scientists to understand this essential form of communication.

However, the extent of the role of chemical cues in settlement and habitat selection for young fish and coral larvae is still unknown.

Fitting In

Coral reefs are home to a broad assortment of organisms, making them one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world. In other words, they contain a wide range of potential chemical cues that could influence settlement. Settlement is when a coral or fish locates a habitat to permanently settle down on. This is a crucial step in the life cycle of most coral reef invertebrates and fishes, as it replenishes coral reefs with new recruits and helps maintain a healthy and biodiverse coral reef ecosystem.

With funding and support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation , a team of scientists, including Dr. Danielle Dixson from the University of Delaware and Dr. Valerie Paul from the Smithsonian Marine Station collaborated on a three-year project to better understand how chemical cues from the reef itself influence fish and coral settlement.

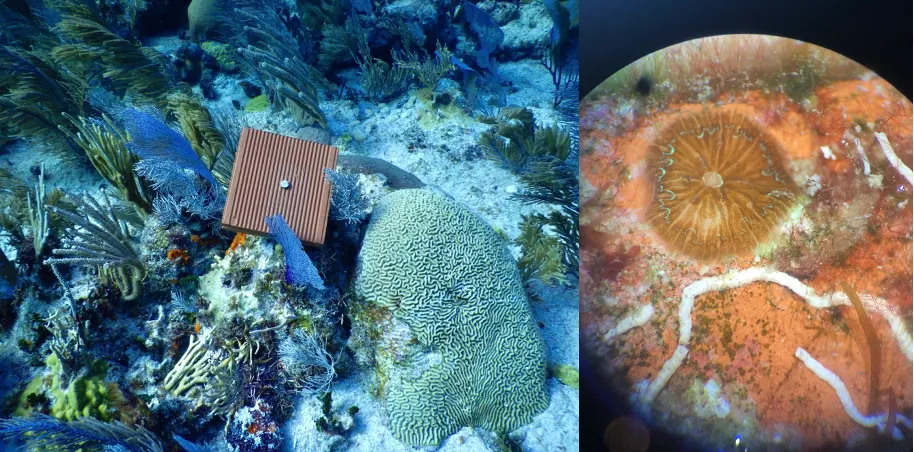

Under the guidance of Paul and Dixson, Dr. Molly Ashur, then a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Delaware, and I conducted experiments at the Smithsonian’s Carrie Bow Cay (CBC) field station, 15 miles off the coast of Belize. Surrounded by healthy and vibrant coral reefs, the field station is an ideal setting for coral settlement research.

“Understanding the connection between environmental chemical cues and larval reef fish recruitment is a critical component of reef restoration, and can inform management decisions and conservation initiatives,” Ashur said.

While it may seem counterintuitive that creatures born on a reef would have trouble finding a place to fit into these communities, it’s a surprisingly complex process. For some coral and fish species, their larvae are carried offshore by ocean currents, where they begin to develop in open water. After that developmental stage, fish larvae then transform into active swimmers in order to locate a suitable coral reef habitat on which to permanently settle. Along the way, they must distinguish between other habitat types and avoid predators.

Testing for Cues

To test organisms’ reaction to various chemical cues on the reef, our team conducted a variety of experiments. In the first two years, we collected samples of anything on the reef around Carrie Bow that could potentially be involved in settlement: water samples around the reef, different species of algae, and samples of common bottom-dwelling, or benthic, organisms. Dr. Skylar Carlson, then a Smithsonian postdoctoral researcher, isolated chemical compounds from these samples for the experiments, and Delaware and Smithsonian research teams then tested their effects on coral larvae and fish behavior.

Paul and Dixson also looked at whole-reef dynamics. One experiment was aimed at understanding how settlement rates on a natural coral reef system might be affected with the addition of Acropora cervicornis and Porites furcata, two coral species common around Carrie Bow Cay. Dr. Molly Ashur and I conducted this experiment from May to November 2019 on six natural patch reefs, which are smaller, isolated reef habitats ideal for field experiments.

Each patch reef was split in half. One side contained transplanted Acropora cervicornis and Porites furcata corals, while the opposite side was left undisturbed to act as a control. Once a month throughout the experiment, Delaware and Smithsonian research teams returned to Carrie Bow Cay to survey the patch reefs to monitor recruitment rates, as well as check on the transplanted corals. Instead of the standard A-F naming convention, we christened each reef with a Harry Potter name —Aragog, Buckbeak, Crookshanks, Dobby, Errol and Fawkes. These whimsical names seemed much more appropriate for the corals’ magical underwater world.

We assessed the effect of the introduced corals over a whole ecosystem by conducting monthly surveys on an abundance of diverse organisms, including bottom-dwelling species; cryptic organisms (those that live in the cracks and crevices of the reef); juvenile fish; and adult reef fish. With this data, we are able to track the abundance of reef fish over the course of the seven-month experiment to get a better understanding of whether the introduction of new corals and their chemical cues may have had an effect on their choice of home on the reef.

In May 2019, we also deployed 10 settlement tile pairs on each side of the patch reefs to track recruitment of coral larvae. These tiles are simply blank slates for young corals to “stick” to or settle down. We collected tiles in November, then tallied the coral larvae to compare coral settlement from both sides of the experimental patch reef.

Additionally, we conducted lab experiments to test the chemical cues in a more controlled environment via a method known as “fluming” -- a research tool used to test the behavioral response of an organism to a chemical cue. We tested juveniles of common reef fish, including damsels, wrasses, parrotfish and grunts to assess how they responded to the chemical cues of Acropora cervicornis and Porites furcata.

Next Steps

Our final result? So far, lots and lots of data.

While we continue to analyze results, one set of preliminary data show that juvenile fish seem to be indifferent in response to chemical cues of Acropora cervicornis and Porites furcata in the fluming experiments. Most fish had neither a strong attraction nor repulsion to the chemical cues. These results are surprising because the juvenile fish were almost always observed around these two particular species, which suggests there is something about them, perhaps their physical structure, that attracts the fish or benefits them in some way.

But as a new area of research, settlement cues offer a rich field of exploration. “Everything was somewhat unexpected since we didn’t know what to expect,” Paul said. “This work could go on for decades and you would still barely scratch the surface.”

Though data analysis continues, and other results are forthcoming, researchers already have gained a deeper understanding of specific preferences among settling fish and coral larvae that will act as a guide for future experiments.

--September 2020