Search

In a scientific first, a deep-sea basket star spontaneously divides

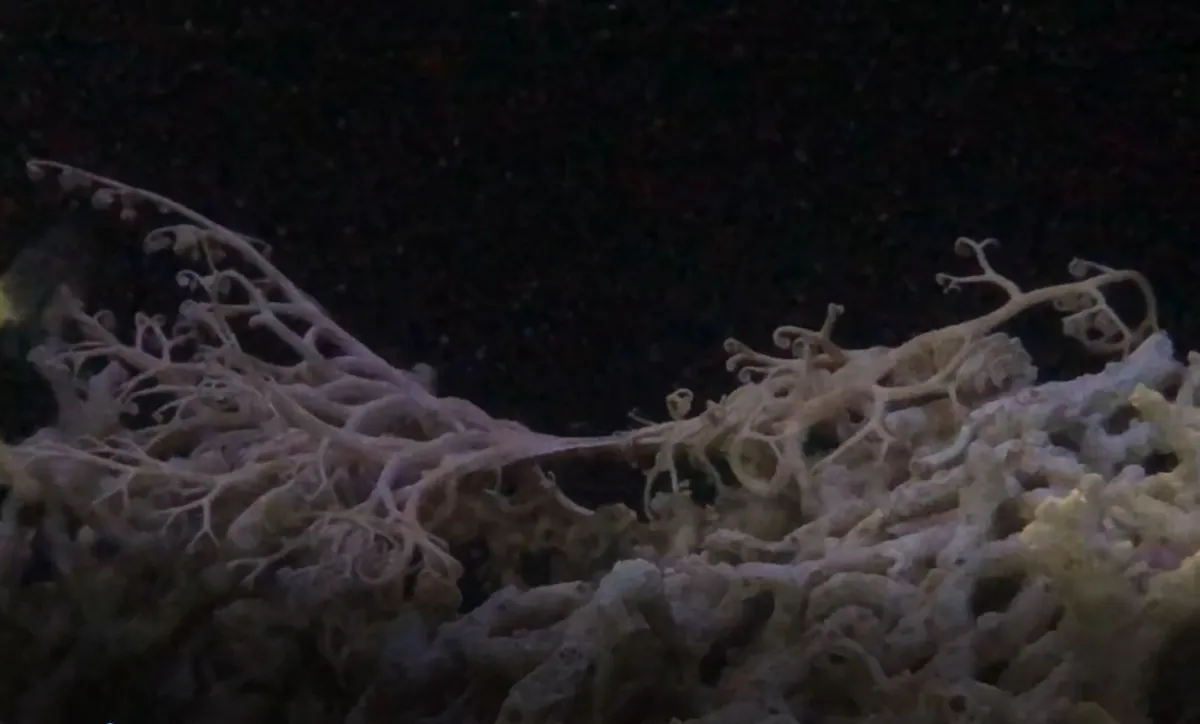

In what is believed to be the first-ever documented behavior in the species, a deep-water basket sea star recently split into two pieces at the Smithsonian aquarium exhibit in south Florida – and both halves continue to feed and thrive months later.

In September, aquarists at the Smithsonian Marine Ecosystems Exhibit (SMEE) at the St. Lucie County Aquarium witnessed the basket star (Astrophyton muricatum) undergo a type of reproduction known as fissiparity, or the spontaneous cleavage into separate parts. Unsure of whether one or both parts would survive, Smithsonian staff continued with regularly scheduled feedings.

“Both parts are responding to food, and that’s a really good sign,” said Bill Hoffman, chief aquarist and manager of the Smithsonian Marine Ecosystems Exhibit.

The two basket stars appear to remain healthy, he added.

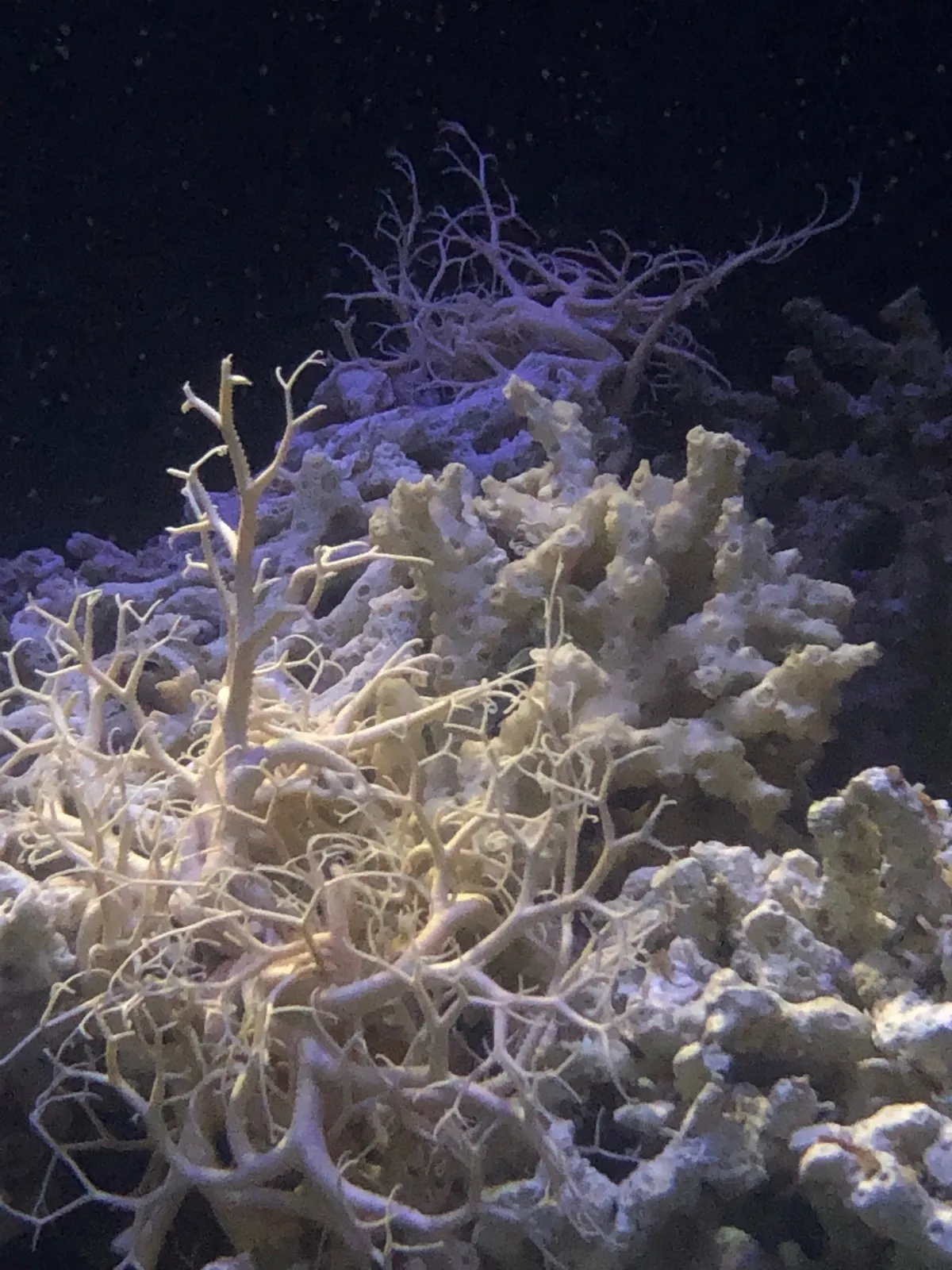

The basket stars are housed in SMEE’s Oculina Banks exhibit, which simulates a unique deep-sea habitat that occurs nowhere else on earth. Formed by a single species of coral, the ivory tree coral (Oculina varicosa)—which can grow into pinnacles up to 30 meters (100 feet) tall at depths of 60 to 90 meters (200 to 300 feet)—these deep reefs are critical habitat for a huge diversity of fish and invertebrates like the basket star.

The original specimen was collected in June 2019 at 60 meters (196 feet) by FAU Harbor Branch researchers including John Reed, one of the original scientists to discovery and study the Oculina Banks. Researchers used a remotely operated underwater vehicle with a manipulator arm to gently collect the basket star.

“We had to keep bringing up buckets of water from the freezer to keep the water cool enough,” Reed said, also recalling that by the time they’d returned to shore, the basket star was clinging to the lid of the bucket, hanging upside down.

Common throughout the Caribbean, the natural range of Astrophyton muricatum extends from South Carolina to Brazil, and it is found at depths from 2 to 500 meters (6 to 1,640 feet). Like many sea creatures, they normally reproduce by simultaneously releasing eggs and sperm into the water, which develop into free-swimming larvae after fertilization.

Basket stars are the ornate cousins of the more common and familiar brittle sea stars. Each arm branches out into multiple smaller offshoots, similar to the roots of a tree. Furled tightly while at rest, basket stars feed by extending their arms into the current to capture planktonic animals, such as copepods and invertebrate larvae.

Dave Pawson, a senior research scientist at Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and an expert in invertebrates including brittle stars, said that while this kind of asexual reproduction has been reported in at least 35 of the estimated 2,000 species of brittle stars, they are generally species that are very small, with the adults being only several millimeters across. This is, to his knowledge, the first evidence that Astrophyton may also be capable of the behavior.

“This species has been observed by thousands of scuba-diving scientists and amateurs over many years, and none have apparently reported asexual reproduction in this species,” Pawson said.

Brittle star and basket star researcher Masanori Okanishi, with the Misaki Marine Biological Station at the University of Tokyo, noted that the observation of a splitting basket star is “amazing.”

“I have reared a species of basket star in our laboratory for more than one year, but I have never seen such phenomenon,” he wrote via e-mail. “No such report is known for at least the large basket star,” adding that he will be very interested in how the new branching arms on each half of the basket stars will regenerate.

Pawson aired a note of caution, however, questioning whether the division may have been a stress response to being collected and relocated in an artificial habitat.

“This question cannot be answered reliably,” Pawson said. “But, I am astonished that it can successfully reproduce by dividing, even in an aquarium.”

--Michelle Z. Donahue and Erin Lomax

November 2019