Search

Smithsonian scientist lauded for pioneering novel ‘reef health’ approach

Smithsonian scientist lauded for pioneering novel ‘reef health’ approach

The award recognizes Dr. Melanie McField’s work to gauge the health of Mesoamerican coral reefs, and her role in building an international coalition to protect them.

By Michelle Z. Donahue

To the casual observer, the Mesoamerican Reef seems to teem with boundless life: jewel-like fishes, curious turtles and numerous other creatures eddy throughout intricate gardens of corals. The reef stretches for more than 700 miles through the Caribbean waters of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras.

But close observers see the many threats and impacts that have diminished the reef over recent decades: bleaching from heat stress, overfishing, inundation by competing algae, runoff from sewers and agriculture. Fish are not as abundant. Entire fields of coral lay in bleach-white piles of ruin, wracked by storms, disease and a warming ocean.

Smithsonian marine biologist Dr. Melanie McField is one of these close observers, determined to understand the myriad threats to the reef and reduce their impacts. But given the magnitude of the pressures, and the sheer size of the reef system, she realized early in her career that only a broad coalition effort could possibly succeed.

For her vision and tireless efforts to develop a user-friendly way to track and measure the reef’s health, and her role in enlisting a multitude of partners to leverage this knowledge to advocate for and advance protections for the reef, the International Coral Reef Society (ICRS) recently awarded McField the 2021 Coral Reef Conservation Award. It is one of the society’s highest accolades.

The world’s only professional association of coral reef scientists, ICRS was founded in 1980 just as reef scientists were beginning to recognize the perilous condition of many of the world’s reefs. The organization’s objective is to promote the creation and dissemination of scientific knowledge and understanding of Earth’s coral reefs.

Belize Beginnings

When McField began working in coral reef systems in Belize in 1990, scientists were already galvanized to understand what was stressing reefs across the Caribbean (and globally) and experimenting with management tools like marine protected areas (MPAs). McField was present for the country’s first mass coral bleaching event in 1995 and quickly organized a monitoring response with MPA staff across the country.

“At that time, we only suspected that heat stress and possibly ultraviolet irradiation were causing bleaching, but we were most concerned about what would happen to these bleached corals,” McField says. “Fortunately, the vast majority of corals did survive. But it was because we were able to get organized and out there quickly to monitor the event as it unfolded that we were able to gain a better understanding of the entire process.”

Belize’s long history in designating natural areas for special protection included MPAs from the 1980s onward. Though MPAs were a step in the right direction, they were mostly being established where beautiful, near-pristine reefs existed, often for the benefit of tourism. McField believed more needed to be done to address other factors that might be driving the need for protections in the first place, such as drifting pollution from land development and agriculture, which could be occurring tens of miles away from the reef itself.

McField also perceived the importance of a more direct connection between ecological research on corals and conservation solutions that benefited not only reefs, but also the communities that depend on those ecosystems for their livelihoods. McField had a unique opportunity to develop this concept further after marine conservation philanthropist Roger Sant posed her a sticky question in 2003: How do we define reef health in such a way that we can quantitively evaluate the success of these conservation measures, and know that those coral reefs are improving?

What would become McField’s career-defining effort, the Healthy Reefs for Healthy People (HRI) initiative, evolved out of this question. After convening a meeting of 25 coral reef scientists in Miami to discuss the concept of reef health, McField co-authored a paper on how to define reef health. The paper eventually snowballed into a 200-page book that outlined 58 potential indicators which could be used to track changes in reef health over time, and formed the foundation of the new discipline.

“Melanie began to think and develop the term ‘reef health’ as a more familiar concept to explain complicated reef monitoring data protocols to local people and policymakers,” said John Ogden, Professor Emeritus of marine biology at the University of South Florida. Ogden served on McField’s doctoral examining committee and also nominated her for the ICRS award.

From an Idea, a Coalition Grows

Though initially the “reef health” concept was dismissed by the coral reef science community as too simplistic, McField’s eye-catching visuals, plain language and easily digestible summaries of reef health that went out in bulletins across the Caribbean simply worked, Ogden says.

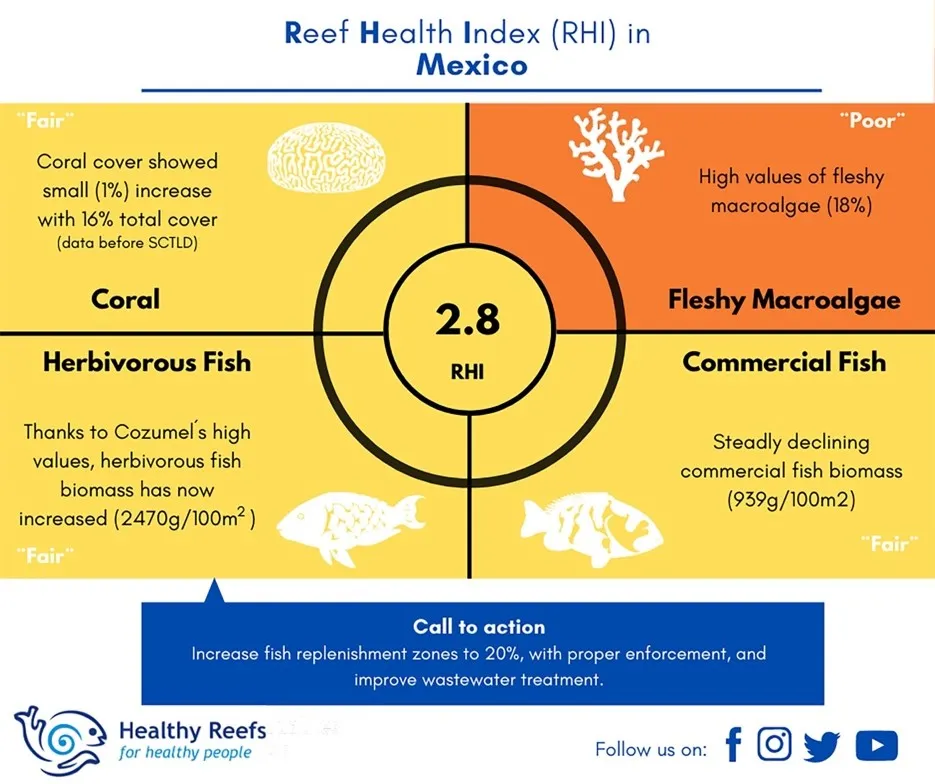

The first Mesoamerican Reef Health Report Card, published in 2008, used seven reef health indicators. Intended to provide a snapshot of a reef’s health at a given moment, indicators consisted of percentage of coral cover, coral disease prevalence, coral recruitment (successful attachment of free-swimming larvae to the ocean floor), the amount of fleshy algae growing on a reef, herbivorous fish abundance, commercial fish abundance, and abundance of long-spined sea urchins (Diadema) on the reef.

Data used in the report were collected from 326 sites throughout Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras, and provided by five initial partners in the region.

But to continue to collect data and empower communities to develop solutions that made the most sense for their local reefs, McField saw the need to get a wide variety of people to willingly participate in the effort.

“We [the coral reef biologists] were having a high old time thinking of reefs as ecosystems, and developing this complicated terminology to describe them, tossing around terms like ‘resilience’ and ‘biodiversity’ – but it was falling on deaf ears of the people who actually used the resources of the reef,” Ogden says.

He adds that McField took a totally different approach. “She invited me and others to a few community meetings and we heard how she just hammered away at the concept of reef health,” Ogden says. “She’s got a lot of personal charm, and a lot of guts, and essentially won’t take no for an answer.”

McField is more circumspect. “Bringing scientists, managers and communities together to agree together to what needs to be done – it’s been a good platform for letting a variety of groups participate and making sure everyone has a voice in saying what we should be recommending,” she says. “We’re trying to manage reefs and conserve them, but this essentially involves managing human behaviors. We need to understand how we can do that better by listening directly to people.”

The HRI network has grown to include over 70 partner organizations across all four of the Mesoamerican Reef nations – including NGOs, government departments and academia. But perhaps more importantly, the focused efforts of HRI’s partnerships have resulted in several significant shifts in national conservation policy in the MAR nations.

HRI’s first Report Card (2008) called for the protection of parrotfish. The call was quickly heeded in Belize (2009) and Bay Islands of Honduras (2010). HRI coordinators in Guatemala and Mexico needed more time to incorporate specific reef data into recommendations that resulted in protections in 2015 and 2018, respectively. Increasing parrotfish populations is a rapid, cost-effective way to improve reef health, as these grazers keep reef-smothering algae in check.

Finally, HRI has been calling attention to the urgent need for improved wastewater treatment, particularly in the coastal communities and tourist centers located in close proximity to coral reefs. These efforts have included supporting new regulations in Quintana Roo, Mexico, as well as in Honduras, which recently signed onto the Cartagena Convention’s Land Based Sources of Marine Pollution protocol. Among other purposes, the protocol standardizes and strengthens wastewater effluent regulations in coral reef areas.

Honing Protections

McField says she is driven in her work by endless questions about how to incorporate new ideas to improve reef health and reach out to additional sectors including private enterprises that benefit from improved reef health.

“Most of the work I’ve done, the questions I’ve been asking, comes from wanting to better understand and measure our impact,” McField says. “I feel a responsibility that our hard work should be making a difference – one that is actually measured on the reef itself.”

How to make the best choices from a dizzying menu of options for reef management must involve both science and direction from the local communities, she adds. Solutions that work in one area may not be the best for another.

“We need to understand the ecosystems—including the human dimensions—so we can manage it better,” McField says. “You learn and keep improving – even if it seems like a never-ending cycle. That’s what adaptive management is.”

Today, the Health Reefs initiative is comprised of 74 partner organizations across the Mesoamerican Reef region. Roughly half are involved in observation and data collection used in the biannual report cards; other partners use the Healthy Reefs data in outreach efforts to communities, businesses and government entities. Looking toward the future, McField says there is room to add other reef health indicators that could include metrics on disease, coral recruitment, mangroves and seagrasses, as well as factors related to climate change.

“The MAR is a whole ecosystem, so she was tying to think: can we monitor it and treat it as such?” says Dr. Helen Fox, conservation science director for the Coral Reef Alliance. The two worked together at the World Wildlife Fund before McField joined the Smithsonian in 2006.

“The Healthy Reefs Initiative is a success story of steady, sustained progress, holding a vision and moving forward,” Fox adds. “HRI and Melanie also are thinking more broadly about what’s next – the new threats coming, how to stay nimble, and promote understanding across many different stakeholders in the MAR ecosystem about the importance of those indicators and what they mean for reef health.”

Belize was an amazing place to start her career in coral reef research and conservation, McField says. It continues to be, with dozens of nonprofits dedicated to environmental and conservation efforts; a nature-based tourism industry that acknowledges the barrier reef as its crown jewel; and a conservation-focused government willing to experiment with management strategies.

Plus, most Belizeans love their coral reef and hold it in high value as part of the nation’s natural heritage.

“You can get in the taxi from the airport and the driver is going to know something about Belize’s corals, says McField. “But you can also have a high-level meeting about reef conservation opportunities with the prime minister because it is that important to the country.”

But, McField warns, coral reef conservationists must sustain their efforts.

“We’re in a difficult fight, with global challenges and trajectories of reef decline,” McField says. “But if we can keep these efforts people-focused and grounded in their approach, and keep reiterating that coral reef conservation is critical for the region – that’s our best strategy to succeed.”

--October 2021