Search

Sharing corals for science

Sharing corals for science

In a year without travel, coral larvae from partners around Florida ensure research can continue

By Michelle Z. Donahue

During a brief window every year in mid-summer, the tropical waters around Carrie Bow Cay, Belize are awash in an ephemeral flurry: it’s coral spawning season, where eggs and sperm are released from their parent colonies in a coordinated mass near the first full moon of August.

In a normal year, the reef and its field station would also be teeming with Smithsonian Marine Station scientists, feverishly collecting what spawn they can before it drifts away in currents or is devoured by predators. The larvae that result from these spawning events are crucial for experiments to better understand the process of how corals settle down to form the very beginnings of reef-building colonies.

But 2020 hasn’t been a normal year, so scientists were absent from Carrie Bow’s spawning season. However, thanks to a network of research partners around Florida, SMS researchers were still able to conduct settlement experiments this year on larvae from corals that spawned in captivity.

The Florida Aquarium provided SMS with nearly 10,000 larvae from the highly endangered pillar coral (Dendrogyra cylindrus), and Biscayne National Park in the Florida Keys contributed larvae from mountainous star coral (Orbicella faveolata). The University of Miami’s Department of Marine Biology and Ecology and SECORE International provided A. cervicornis larvae.

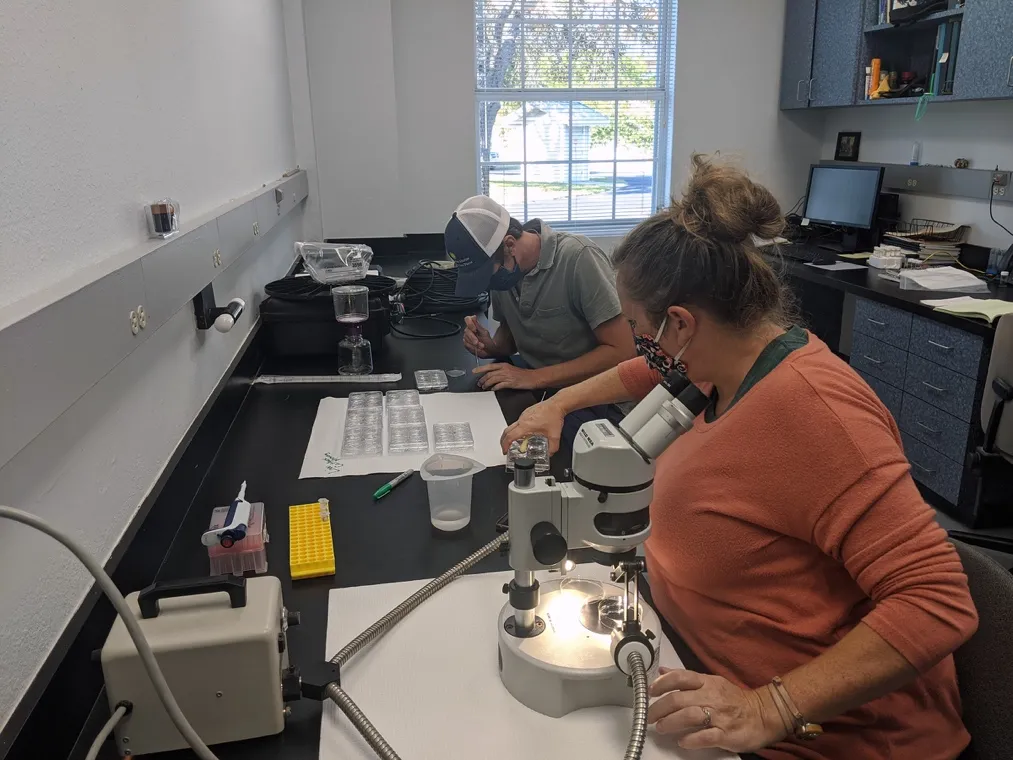

“Despite not being able to travel and dive for coral spawning, we’ve been able to work with partners throughout the state, and come together so that we could run these experiments,” said Dr. Jennifer Sneed, an SMS chemical ecologist who studies coral settlement. “We’re excited to use teamwork to still be able to get things done.”

For each coral species, Sneed and SMS Director Dr. Valerie Paul dosed them with varying concentrations of the compound tetrabromopyrrole. Also known as TBP, it is extracted from a bacterium that grows on crustose coralline algae (CCA). Resembling splashes of pink paint on rocks and other surfaces, CCA provides an attractive surface upon which coral larvae frequently settle to metamorphose into coral polyps. This year’s supply of TBP was provided by another collaborator, Dr. Vinayak Agarwal at Georgia Institute of Technology, who synthesized the compound and several related compounds to test their effectiveness.

Sneed has previously shown that TBP alone can prompt the settlement of larvae of some corals, including other Orbicella and Acropora species. The hope is that the lab-based TBP treatments may offer clues for developing new methods to make it easier to induce coral settlement for restoration purposes, which would accelerate efforts to conserve and restore threatened wild coral reefs.

Sneed noted that though results are still preliminary, the experiments did confirm that TBP does induce settlement in O. faveolata, D. cylindrus and A. cervicornis, which had not been previously documented.

Several of the experiments also involved testing TBP on a variety of substrates, or tiles, upon which coral spat can settle. Star-shaped substrates, provided by the coral conservation organization SECORE International, were a particular focus. SECORE currently “conditions” these tiles to prepare them for laboratory coral settlement; the process involves a month in the open ocean to allow CCA to accumulate, after which they are placed into large kiddie pools along with free-swimming larvae. Once larvae have attached themselves and begun to develop into small colonies, these tiles can be placed around reefs as part of restoration projects

By finding a way to load the tiles with an attractive chemical cue such as TBP that prompts larvae to readily settle, SECORE and other organizations may eventually be able to speed up the settlement process by skipping the offshore conditioning currently required for the substrate tiles.

“If we can get to the right cues to get the larvae to settle out, then we can use that to scale up restoration efforts,” Paul said.

The research team was also shocked by the longevity of some of the coral swimmers: while most coral larvae of the species in question settle down in a matter of days, some were still happily swimming around more than 20 days after arriving at SMS.

“We’ll run experiments until we run out of larvae, or until they decide to settle without the cues,” Paul said.

Sneed JM, Sharp KH, Ritchie KB, Paul VJ. 2014 The chemical cue tetrabromopyrrole from a biofilm bacterium induces settlement of multiple Caribbean corals. Proc. R. Soc. B 281: 20133086. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.3086

--September 2020