Image

DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY

(July 1853 - March 1854)

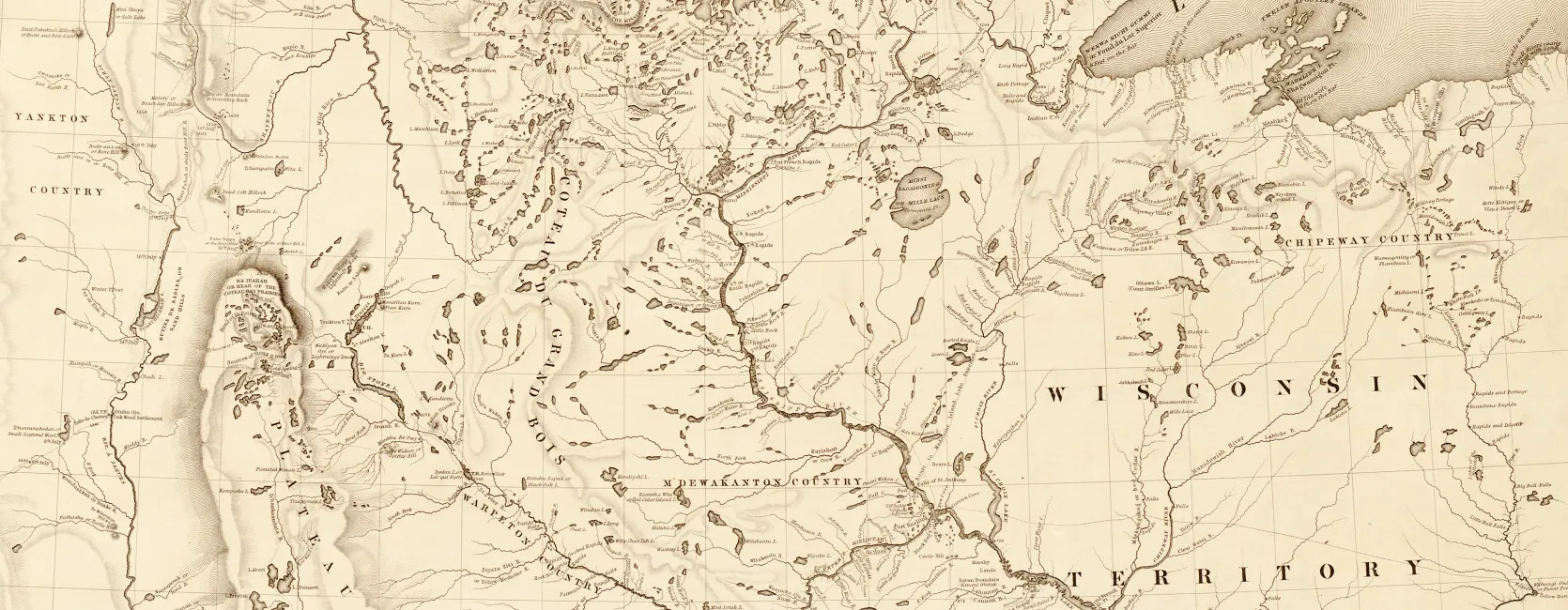

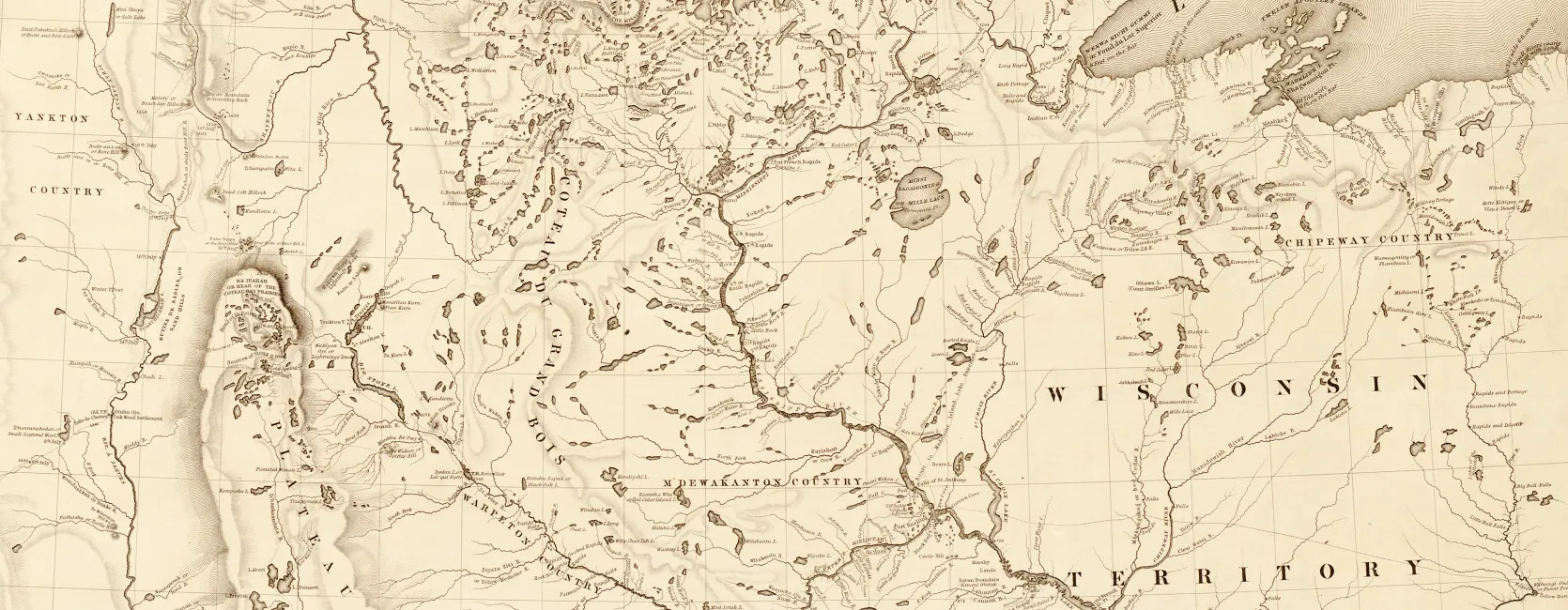

Expedition botanist John M. Bigelow kept the purpose of the Whipple expedition—finding a railroad route from the Mississippi to the Pacific—in the forefront of his mind while examining plants. He documented how different species could be an asset to the creation of the railroad, noting that Douglas spruce (Abies douglasii) was plentiful, and could be used to make railroad ties, “equal, if not superior, to those of any other wood in the West.”

The expedition was one of six major expeditions that traversed through different parts of the country in search of a promising railroad route. Twelve scientists, including Bigelow, traveled with the expedition party along the 35th parallel through modern-day Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. Spencer Baird, assistant-secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, recommended Bigelow for the position of botanist on the expedition.

Antoine Leroux, an experienced western guide knowledgeable of the Native American uses for plants, joined the expedition at Mojave territory in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The Mojaves helped the scientists collect botanical, biological, and geological specimens, and believed that the railroad would result in a valuable trade route spanning their territory.

Bigelow collected a considerable number of cacti on the journey, and stated that, at the time, “the Cactaceae have not heretofore been well studied in the United States, Dr. Engelmann, of St. Louis, being almost the only botanist who has paid any special attention to them.” The Santa Maria Valley, located in modern day Arizona, was named the “region of cacti” by the expedition members, and yielded specimens of Echinocactus wislizeni. The juice of this plant works as a substitute for water and was known to the explorers as having saved the lives of dehydrated trappers in the region. The explorers found a puzzling specimen of this cactus left by the Yampai Indians in which the spines were burned and the insides had been hollowed out. Leroux explained that the Yampai tribe scooped out the insides of the cactus, added vegetables, and used the cactus as a kettle over a heated stone.

Though Bigelow collected numerous plants from the Cactaceae family, other types of plants were also plentiful. The golden suncup Oenothera brevipes was discovered on gravel hills near the Colorado River, and the widely spread wild onion Allium amplectens was discovered on the hillsides in Sonoma, California. Bigelow was the first to identify the adult female flowers of the willow Salix bigelovii (renamed Salix lasiolepis), or Bigelow’s willow, though he previously collected these plants in a younger stage of development. The annual herb Mimulus whipplei, or Whipple’s monkey-flower, was also discovered and named after the expedition leader. Though native to California, today the monkey-flower is believed to be extinct.

In the winter months, the scientists had difficulty collecting botanical specimens. Bigelow explained that their time in Zuni Valley was during the “most unpropitious season of the whole year for the collection of herbaceous plants.” They did, however, find a new species of cactus in the genus Opuntia in Zuni Valley. Bigelow stated that, “as this tribe of interesting plants was almost the only one we could find and study, at this late season of the year, our party rivaled each other in daily bringing some of them into camp that had not been before seen or collected.” Opuntia davisii was named after Secretary of War, Colonel Jefferson Davis “under whose auspices the expeditions for the exploration of a proper route for the Pacific Railroad were organized, and were able to accomplish so much, not only for this specific object, but also for the elucidation of the natural history of this hitherto almost unknown country.”

Despite the seasonal struggles, Botanist John Torrey—who classified the plants Bigelow collected—writes that Bigelow’s “ample collections were brought home in perfect order. A number of new genera and more than 60 new species have been discovered by Dr. Bigelow and he has added much valuable information upon many heretofore imperfectly known plants.”

References:

Bigelow, John M. Route near the thirty-fifth parallel, explored by Lieutenant A.W. Whipple, topographical engineers, in 1853 and 1854. Report on the botany of the expedition. Washington D.C.: WarDepartment, 1856.

Foreman, Grant. A Pathfinder in the Southwest. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941.

Goetzmann, W.H. Army Exploration in the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

Goetzmann, W. H. Exploration and Empire. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1966.

Hafen, LeRoy R. The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West. Glendale, California: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1966. Vol IV.

Senate. Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Washington: Beverly Tucker, 1855.

Sherburne, John P. and M.M. Gordon. Through Indian Country to California: John P. Sherburne’s Diary of the Whipple Expedition // edited by Mary McDougall Gordon. Chicago: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Sherer, Lorraine M. Bitterness Road: The Mojave: 1604 to 1860. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press, 1994.

Waller, A.E. “Dr. John Milton Bigelow, 1804-1878. An Early Ohio Physician- Botanist.” Ohio Historical Society,1998. http://resources.ohiohistory.org/ohj/browse/displaypages.php?display[]=0051&display[]=313&display[]=331

Whipple, Lt. Amiel Weeks. Reports of Exploration and Surveys, to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Washington: A.O.P.Nicholson, 1856.