Image

DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY

(1853-1855)

The Stevens Pacific Railroad Survey brought three naturalists into the wilderness of Washington Territory. The expedition significantly enhanced our knowledge of the environment of the northwestern United States, where vast tracts of land sat uninhabited and little scientific exploration had occurred. Naturalist James G. Cooper, described the landscape as being strikingly different than that of the Atlantic coast and inexpressible in its majesty. He states, “this noble scenery is found to be accompanied by a proportionately gigantic vegetation, and, indeed, everything seems planned on a gigantic scale of twice the dimensions to which we have been accustomed.” He goes on to say, “Nothing seems wanting but the presence of civilized man, though it must be acknowledged that he oftener mars than improves the lovely face of nature.”

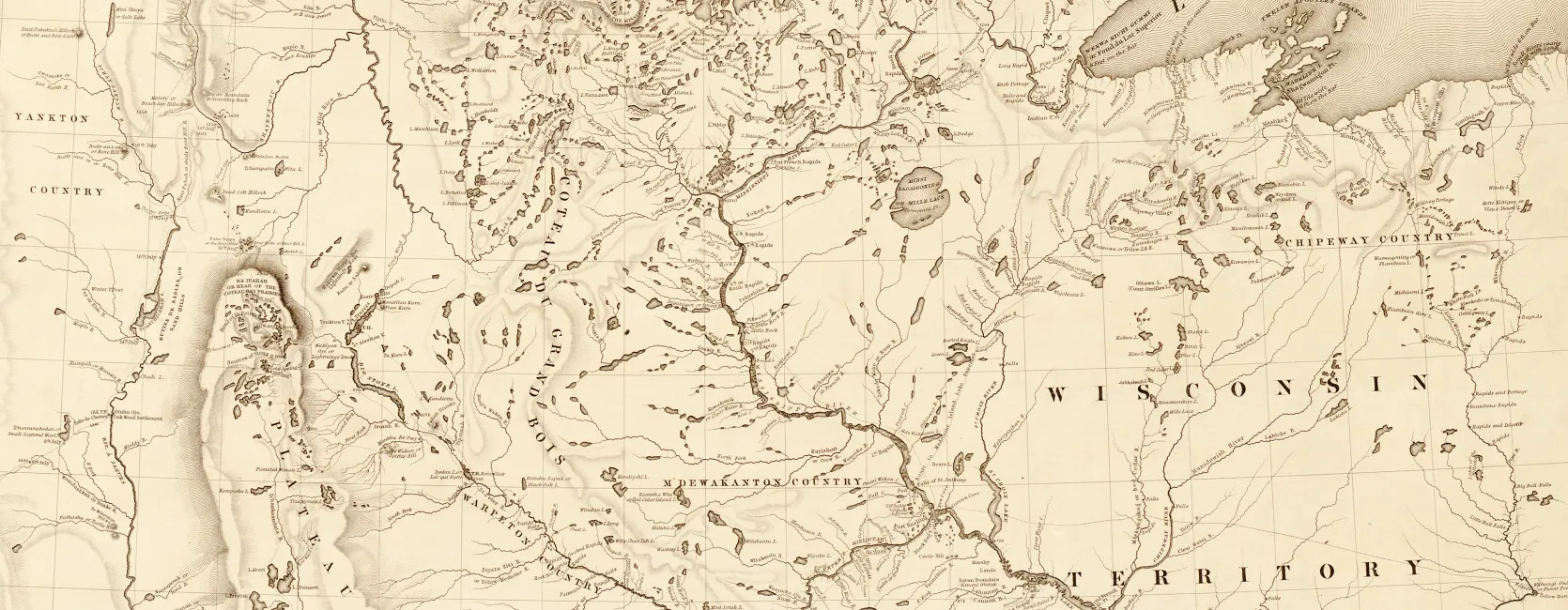

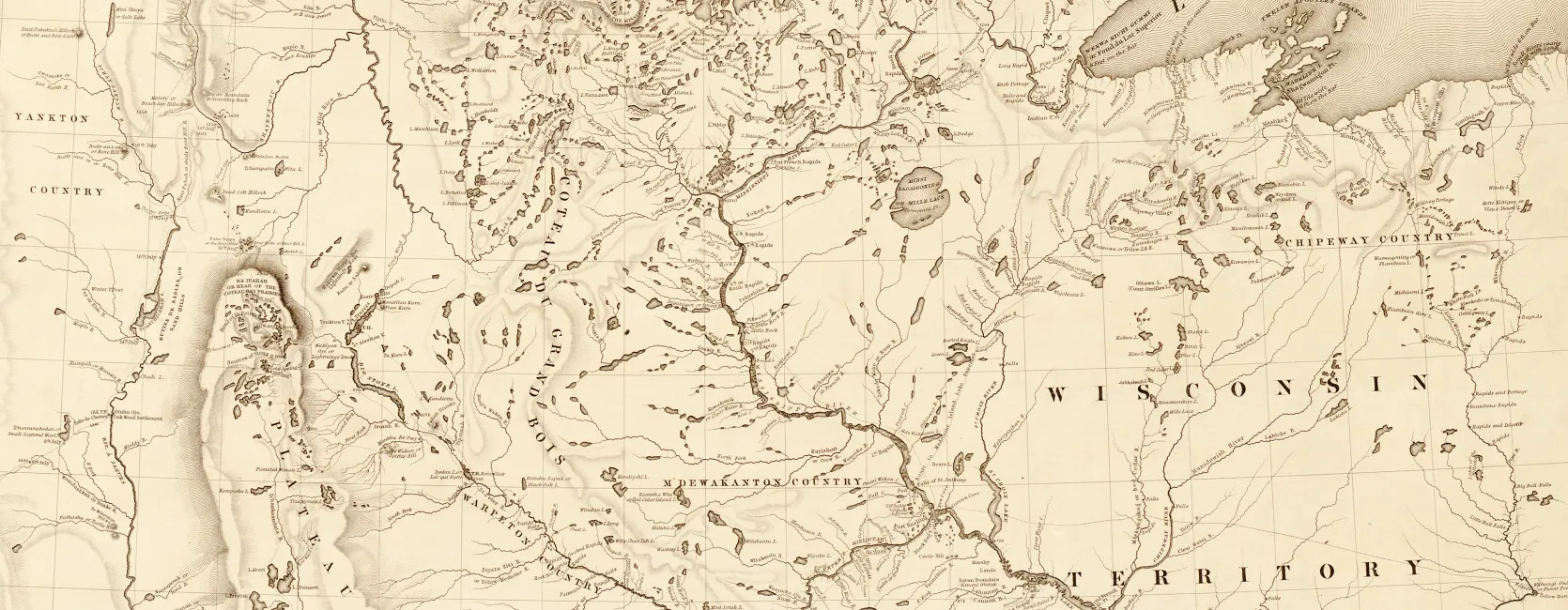

This insight was expressed in 1853; that same year, Congress allotted $150,000 towards six expeditions to find the most practical path to carry a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Governor Isaac I. Stevens led the northern-most survey along the 47th to 49th parallels.

Due to the difficult terrain, the expedition was divided into two divisions, which later converged at the Columbia Basin. The eastern division was led by Stevens and was accompanied by Naturalist George Suckley. The division traveled east of the Rocky Mountains, documenting three new species and one new genus (Endelopis) along the way. Since this area had been explored previously, many species, such as Veronica peregrine and Rumex venosus, had already been described. These specimens, however, were still interesting to compare to those collected by the western division, and were sent to the Smithsonian.

The western division, which commenced from Washington Territory and explored potential passes through the Cascade Mountains, was led by Captain George B. McClellan and was accompanied by naturalists George Gibbs and James G. Cooper. Cooper compiled his observations of the expedition in many papers, including one entitled “Report on the Botany of the Route.” As the expedition progressed westward, Cooper described the Cascade Mountains as, “a scene probably unsurpassed in magnificence by any in America.” Unfortunately, Cooper did not have adequate time to fully document the beautiful region. He did, however, notice the subalpine plant Juniperus communis, several varieties of berries (including the newly discovered Vaccinium membranaceum), and many colorful flowers that dotted the landscape and led Cooper to observe that it “looked more like a garden than a wild mountain summit covered for nearly half the year with snow.”

Next, the expedition moved into the Great Plains region near the Columbia River. Many of Cooper’s observations pertained to agricultural possibilities, such as where irrigation would be needed and the quality of the soil. He collected two new plant species, Astragalus miser var. serotinus and Crepis cappillaris, in this region.

Cooper documented 360 species west of the Cascades, including the bellflower Campanula scouleri, gathered from under the shade of fir trees. 150 of these species were unique to the prairies. The prairies were bordered by forests with mature trees and Cooper observed that “from February to July [the prairies] look like gardens, such is the brilliancy and variety of the flowers with which they are adorned. The weary traveler, toiling through the forests, is sure to find in them game, or, at least, some life to relieve the gloomy silence of the woods.”

Perhaps the gloomy silence of the forest became a bit more bearable when Cooper declared that the forest was “one of the principal sources of commercial wealth to the Territory.” He describes the Oregon cedar (Thuja plicata) as a lightweight and soft tree. The Indians chopped it using stone hatchets and crabapple wedges and formed the trunk into canoes. He states that, “A backwoodsman, with his axe alone, can, in a few days, make out one of these cedars a comfortable cabin, splitting it into timbers and boards with the greatest ease.” Other trees could be utilized as well; the sap of the white maple (Acer macrophyllum) could be used for sugar and the wood of Oregon alder (Alnus rubra) could be used to make furniture. Botanists were just beginning to understand the many treasures that could be found in the northwestern United States during the time of the Stevens Expedition.

References:

Anderson, Alice Racer, editor. Plant Life of Washington Territory: Northern Pacific Railroad Survey, Botanical Report, 1853-1861. Washington Native Plant Society, 1994.

Coan, Eugene. James Graham Cooper, Pioneer Western Naturalist. University Press of Idaho,

1982.

Cooper, J.G. The natural history of Washington territory, with much relating to Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oregon, and California, between the thirty-sixth and forty-ninth parallels of latitude…New York: Bailliere Brothers, 1859.

Foreman, Grant. A Pathfinder in the Southwest. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma

Press, 1941.

Goetzmann, W.H. Army Exploration in the American West. New Haven: Yale University Press,

1959.

Sherburne, John P. and M.M. Gordon. Through Indian Country to California: John P.Sherburne’s Diary of the Whipple Expedition // edited by Mary McDougall Gordon. Chicago: Stanford University Press, 1988.