Image

(1860 - 1874)

Click here for California Geological Survey Collections

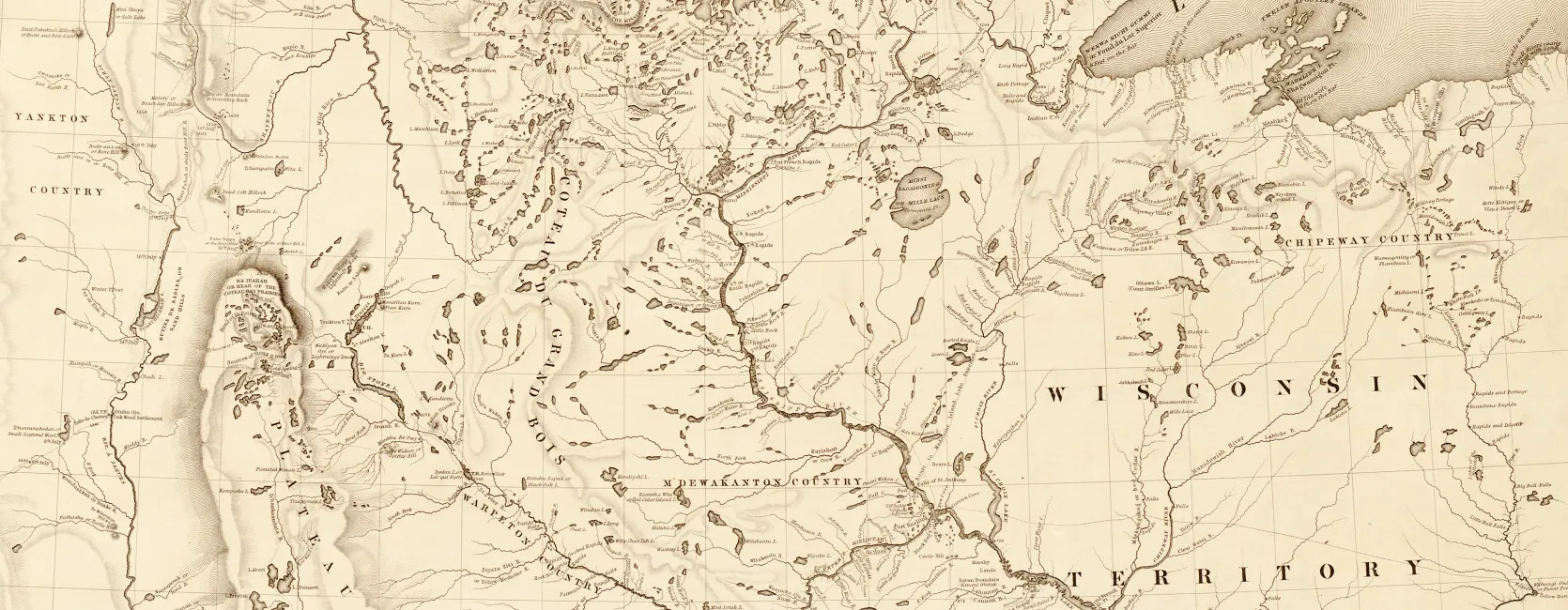

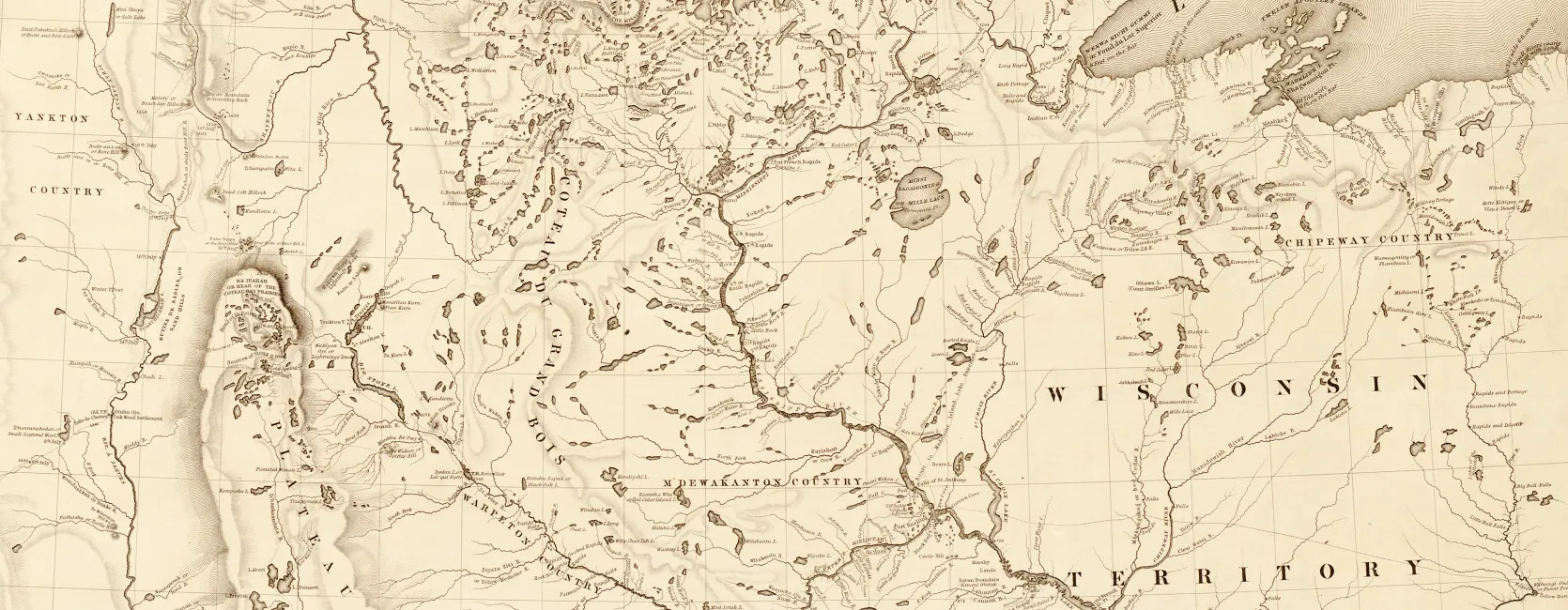

California is home to an abundance of extraordinary natural resources. In addition to the gold that incited the California gold rush, the state contains mountains and deserts teeming with plant life. Redwood and giant sequoia trees tower 200 or 300 feet high, while cacti and sagebrush grow in deserts with almost no rainfall. In the late 1850s, the gold rush was waning, but Californians still hoped to discover valuable natural resources in their state.

William Brewer and Party

The California Geological Survey, headed by Josiah D. Whitney, was created by the state legislature in 1860 and lasted until 1874. William H. Brewer and Henry N. Bolander were the main field botanists, although many other naturalists contributed to the collection and description of the survey’s plants. Brewer, who also served as First Assistant to Whitney, was the head botanist from 1860 to 1864 and “the first to botanize to any considerable extent in the high Sierras.” He took detailed observations and field notes, and wrote a journal in the form of a series of letters home. These letters told of his travel experiences and included descriptions of the habitats and vegetation he encountered.

Survey Party including Brewer and Whitney

Brewer found many beautiful and unusual plants across California. Near Mount Shasta he collected the California pitcher plant (Darlingtonia californica), a carnivorous plant also known as the cobra lily, which is now classified as a threatened species. He also found the valley oak (Quercus lobata), a species “noble indeed,” with “large limbs branching in … great round curves, great Roman arches of thirty to fifty feet span.”

Brewer noted in particular the unique botanical features of Californian deserts and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He described the desert as “a great plain … sandy, but with clay enough in the sand to keep most of it firm, and covered with a scanty and scattered shrubby vegetation.” Despite receiving less than an inch of rainfall per year, “[t]he Californian deserts are clothed in vegetation” with plants such as sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) and various species of yucca. Brewer apparently disliked the creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), “every part of which stinks, making the whole air offensive,” but described the moundlily yucca (Yucca gloriosa) as “truly magnificent when in flower.” Brewer also noted a distinct progression of flora in the Sierra Nevada Mountains as altitude increased. The highest range of elevation was dominated by the white bark pine (Pinus albicaulis), a shrubby tree that could survive up to 11,000 feet in elevation. According to Brewer, “[i]ts branches are very tough and it will grow where fifty feet of snow falls on it every winter”.

Such hardy trees may have intrigued Brewer, but he was most impressed by California’s “Giant Trees,” the redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), which he called the “grand wonders of the vegetable world.” The redwoods grew “ten to fifteen feet in diameter, and over two hundred feet in height.” New trees sometimes grew on top of fallen ones, resulting in grown trees with bases over ten feet above the ground and “great arches of roots” once the fallen tree underneath had decomposed. Brewer encountered giant sequoia trees in the Sierra Nevada Mountains even larger than the redwoods. Many of these trees were over 300 feet high, and Whitney estimated that one fallen tree was over 1,255 years old. Some of the fallen, hollow tree trunks were spacious enough to ride through on horseback.

When Brewer left the survey in 1864, he returned to the eastern United States and began making arrangements for the compilation of the botanical report. During the seasons of 1866 and 1867, Bolander replaced him as the head field botanist on the expedition, while several other naturalists collected specimens in various locations throughout California. Various botanical experts, including Harvard Botanist Asa Gray, contributed to the classification and description of the specimens collected on the survey. These were compiled to be published in the expedition’s botanical report, but before the report had been completed, the California Legislature cut funding for the California Geological Survey in 1874. Fortunately, several private citizens of San Francisco donated the necessary funds, and the valuable botanical information obtained during the historic survey was published in 1876.

References:

Brewer, William H., edited by Francis P. Farquhar. Up and Down California in 1860-1864: The Journal of William H. Brewer, Professor of Agriculture in the Sheffield Scientific School from 1864 to 1903. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

Brewer, William H.; Watson, Sereno; Gray, Asa; and J. D. Whitney. Botany. Cambridge, Massachusetts: John Wilson and Son, University Press, 1880.

Block, Robert Harry. “The Whitney Survey of California, 1860-74: A Study of Environmental Science and Exploration: A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography.” PhD diss,. University of California Los Angeles, 1982.

Fire Effects Information Database. USDA Forest Service. Plant Species Life Form: “Darlingtonia californica.” http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/ (for information on species Darlingtonia californica; accessed July 27, 2010).

Merrill, George P. Contributions to a History of American State Geological and Natural History Surveys. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1920.

New York Botanical Garden: Archives and Manuscripts: Merntz Library. “William Henry Brewer Papers (PP) Brewer, William Henry 1828-1910.” New York Botanical Garden, Merntz Library, 2005. http://www.nybg.org/finding_guide/archv/brewer_ppb.html.