Search

News from Recovering voices

Welcoming the Wauja Women

By: Jab'ellalih Ixmatá Schaaff, Emilienne Ireland, and Phil Tajitsu Nash

10/29/2024

From July 10-July 16, Recovering Voices hosted three Indigenous Wauja women from two villages in the Amazon basin, Piyulewene and Piyulaga. This project is a continuation of a 2016 Recovering Voices visit that brought three Wauja men to the Smithsonian.

The Wauja reside in seven villages in the Xingu Indigenous Territory, a region consisting of tropical savannah and rainforest in central Brazil. The Wauja are one of 16 culturally and linguistically distinct Indigenous peoples that comprise the Upper Xingu culture area. The Wauja language is a member of the Arawak language family, which includes languages spoken in lowland Amazonia and elsewhere in South America, as well as the Caribbean and parts of Central America.

Project participants Pere Yelakiwaurá and Yakakumalu Waurá are two elder Wauja women who are especially knowledgeable tradition and culture bearers in their community. These women were both raised in chiefly households, receiving extensive specialized training in Wauja history, oral literature, and sacred ritual. The two elders were accompanied by Keiru, a young Wauja village schoolteacher who speaks Portuguese and Wauja fluently, and who has expressed interest in documenting her culture. Her participation was critical, because the elders had no prior experience traveling in big cities and navigating a world with signs and interactions that required a knowledge of non-Wauja languages.

Anthropologist Emilienne Ireland, a Smithsonian Research Associate, and her husband Phil Tajitsu Nash, who teaches Asian American Studies at the University of Maryland, organized both the Wauja men’s visit in 2016 and the Wauja women’s visit in 2024, hosting each group in their home for six weeks. Ireland has maintained a close relationship with the Wauja since first visiting the Wauja community in 1981, and Nash has worked with her on Wauja projects for over three decades. Together, they have collaborated with the Wauja community to document the rapid cultural changes the Wauja have experienced. These include adopting a currency-based economy rather than a redistributive one, and having young Wauja learn in Portuguese-based Brazilian schools rather than learning from Wauja elders around the campfire or while hunting, fishing, and performing agricultural tasks.

As a result of these changes, many of the hand-made objects in widespread and everyday use forty years ago are no longer made or used, having been replaced with manufactured tools and household items that reflect greater integration with the national economy. Consequently, the rich context associated with these traditional objects, made by hand using only materials provided by local forests, fields and rivers, must be described and recorded for future generations. This context includes traditional stories, personal recollections, techniques of manufacture, materials, designs, ritual significance, esthetic criteria for excellence, everyday uses and the social relations of circulation via gifts, sharing, exchange, and payment.

The goal of the 2024 project is to document female domains of knowledge and provide insight into the gendered differences between male and female domains of knowledge, while also emphasizing the significance of preserving Indigenous language and traditional knowledge. It allows future generations of Wauja to become full participants in the national society of Brazil while maintaining knowledge of and connection to their ancestral traditions. It encourages current and future Wauja youth to reflect on the data collected and apply the elder women’s traditional knowledge to their own lives.

In 2016, the Wauja men visited the Smithsonian’s 600-object collection of Wauja artifacts, which was collected by Ireland from 1981 to the present day. The men were filmed as they discussed how Wauja items in the collection were created, stored, and used – and how the designs and symbols were relevant to Wauja culture. When discussing women’s garments, cooking implements, and other objects that were more related to women’s ceremonial and work life, however, the men sometimes remarked, “it would be best if the women explained that.”

Throughout the six-week visit, the Wauja women dedicated many hours to making videos describing and analyzing objects in the Smithsonian’s Wauja collection. Roughly five dozen Wauja ceramic zoomorphic pots produced by Wauja ceramic artists were analyzed and discussed first in Wauja by the two elders. Then Keiru the schoolteacher added her commentary in Portuguese. Finally, Emi Ireland, who speaks both Wauja and Portuguese, was able to translate key aspects of the prior comments into English while also adding insights gained in her 43 years of interaction with the Wauja community.

A notable aspect of these bowls is how they resemble the natural world. They have practical functions such as cooking, eating and storage vessels, but they also reflect the zoological life of the region. Beetles, anteaters, turtles, bats and other beings encountered in the natural world were among the creatures represented. The pots in this collection are mostly two-toned: a burnt orange color contrasting against a black interior where food would be placed. The women noted that as they fed these representations of forest animals by putting food in their bellies, the forest also fed them in return.

These baskets are also from the Ireland collection at the Smithsonian. The Wauja women reflected on their own childhoods, when they used baskets like these to carry or store many kinds of things – manioc tubers from their gardens, ripe pequi fruit gathered in their orchards, hand-spun cotton thread, shell necklaces worn in ceremonies, belts of the kind that women wear, made from fine strands of twisted buriti palm fiber and fastened around the hips. Yakakumalu noted that the smaller baskets were made for little girls who had not yet reached puberty. Once she entered adolescence, a young woman graduated to a basket large and sturdy enough to enable her to skillfully carry heavy loads on her head.

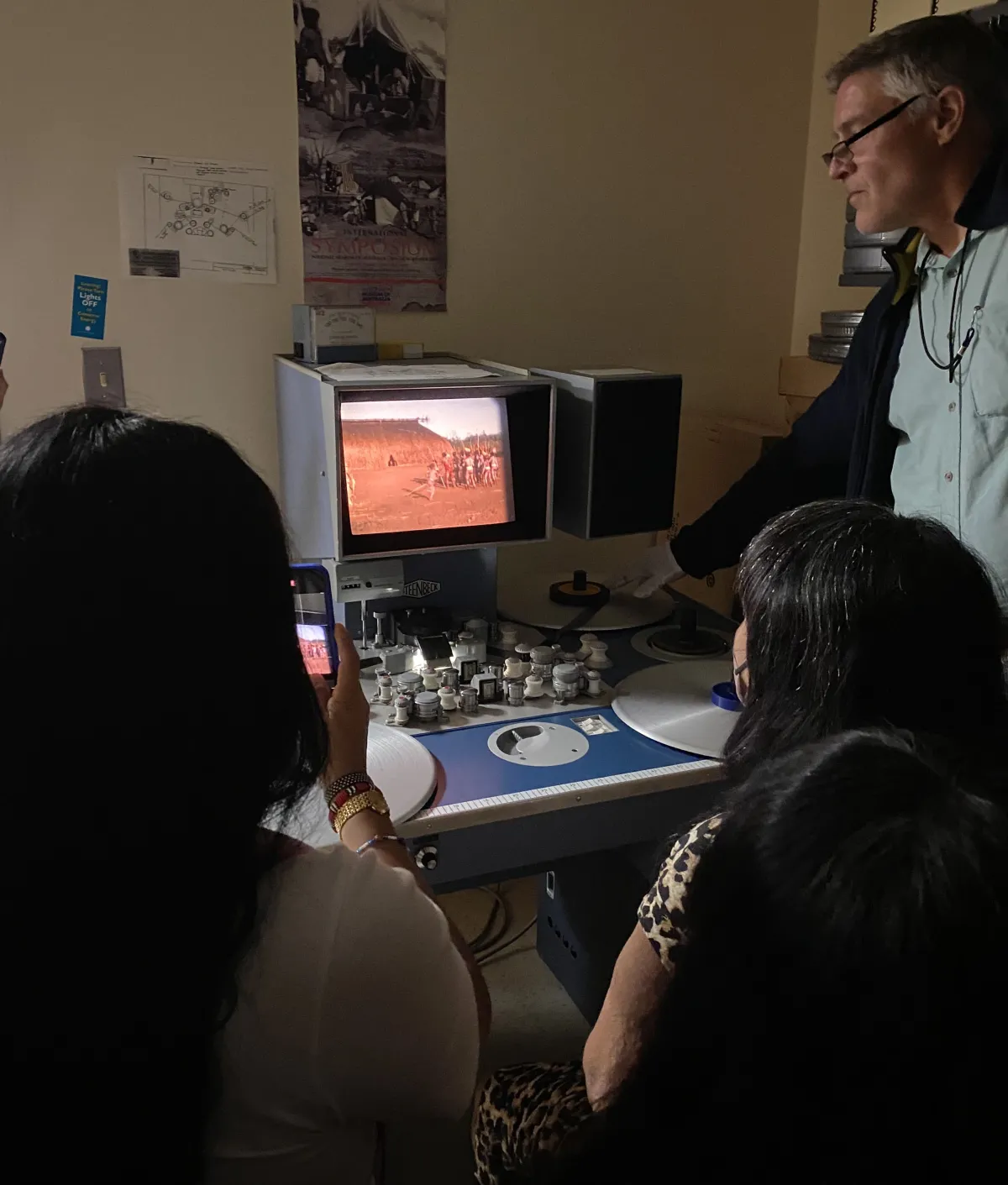

In addition to making videos that described the baskets, pottery, and other objects, the women also were able to engage with a part of their own personal history. Harold Schultz’s series of short films, along with many other digital treasures, are housed in the Smithsonian’s Human Studies Film Archives (HSFA). Brazilian ethnographer Harold Schultz created a series of short films of the Wauja in 1964, which featured Pere’s late father and Yakakumalu’s late grandfather. While the women had seen digitized versions of the videos before, this visit offered them the opportunity to visit the HSFA to see the videos in the context of the museum and the work they were doing each day to record their own history. Museum Specialist Mark White, an HSFA leader who had met with the Wauja men in 2016, was back again to show the women their family members on film. The women watched two films from the Schultz collection at the HSFA: « Javari » Competition Game (Training) 1964 and Wrestling Match 1964.The women’s reactions were recorded, including the identification of long-departed elders whose names and histories would certainly have been lost if these elders had not been brought to the Smithsonian.

Digital technology arrived very recently in the Wauja community. The two elder women grew up and received a traditional education in a time before computers, digital cameras, and cellphones. The Wauja transmitted knowledge orally and through shared experience. Only a few decades later, their grandchildren are growing up fully immersed in an interconnected world. Cell phones, digital video, and even international video calls are now available to Wauja living in the Amazon rainforest. The Wauja also use aerial camera drones to monitor their territory, NASA imagery to track wildfires in nearby regions, and online social media to stay in touch with relatives in other villages, and even anthropologists living abroad.

Because of these changes, Wauja have become more comfortable with the prospect of watching old clips of their ancestors. Forty years ago, seeing old videos and photos was considered disrespectful to the dead, as things once belonging to the deceased – including images of the deceased – were considered capable of calling the spirit of the dead person back to earth, instead of allowing it to ascend to the village in the sky where ancestors feast and dance. Years ago, however, when the Wauja realized that a photo of their loved ones existed, they began to ask to have a copy, provided it was kept discreetly covered in a closed folder, and only opened briefly now and then. Over time, the comfort of seeing images of loved ones has overtaken the reluctance to display them. Nowadays, in many houses, images of deceased loved ones are lovingly displayed.

Their second week working with Recovering Voices brought the Wauja women to the Natural History Building on the National Mall in downtown DC. Since it is open to the public, the Natural History Building is the face of NMNH, but inside its walls there are still many secrets to be discovered, including the entomology (insect) and ornithology (bird) departments.

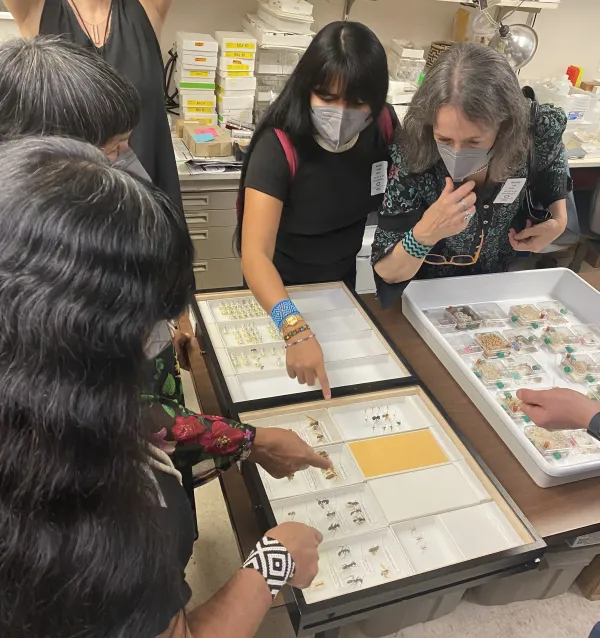

Entomology department co-chair Sean Brady and post-doc fellow Jeffrey Sosa-Calvo showed the women various ant specimens from central Brazil. Of course, Sean and Jeffrey are the specimen experts, but the Wauja women are local field experts from the forest where the ants were collected. The still, lifeless specimens in the Smithsonian labs are living creatures in their daily lives. The women described in Wauja, translated into Portuguese and English, where the ants are found, how they live, and their names in the Wauja language.

It was a clear reminder that the science of entomology and the living cultures and languages of people inhabiting the collection areas are both essential to fully understanding the specimens and their place in the local biosphere. For example, the Paraponera clavata otherwise known as the bullet ant, is a common species of ant found in South America and the Amazonian rainforest. These Wauja women were very familiar with this species due its particularly memorable sting. Sometimes described like the sensation of being shot, hence the nickname “bullet ant,” the sting of Paraponera clavata can be all-consuming for a period of up to 24 hours.

The Wauja women, like the men before them, were also welcomed to the bird department. They were shown a variety of birds from Amazonia that would be found specifically in their region. Ornithology chair Christopher Milensky pulled the specimens from the collection cabinets and invited the women to share their knowledge of each species.

Immediately, the Wauja women huddled and pointed excitedly at the bird specimens. Within seconds, the specimens were no longer merely dead objects. They seemed to come to life in the screeches, caws and trills coming from the women. This is how they most easily identified the birds: not only by name, but also by the sound each bird produced. At one point Dr. Milensky pulled out a bird call app on his phone, and when he selected a a bird that the Wauja had just described, the app provided a recorded bird call that was exactly as the Wauja had just demonstrated.

The Wauja women also remarked how climate change has modified the natural landscape of their region. The recurrent wildfires and increasing temperatures of recent years have resulted in the loss of many once-familiar bird species from their region. As a result, some birds described in their sacred stories are no longer seen, while new birds have appeared that are not mentioned in local stories and whose vocalizations are not known by the Wauja.

On the final week of the project, Recovering Voices staff was invited to a dinner hosted by Emi Ireland and Phil Tajitsu Nash. This relaxed environment allowed for the women to show off their beadwork and pottery. It also provided an opportunity for the Wauja women to describe their thoughts on their time at the Smithsonian. Keiru, the young school teacher, remarked how this visit was meaningful not only to connect with her own Wauja culture, but also opened her world to other Indigenous cultures, including the Navajo, Piscataway, Chickasaw, Yup’ik and other North American Indigenous cultures represented at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival, sponsored by the National Museum of the American Indian. She also emphasized the importance of the trip as a way to demonstrate the importance of women’s knowledge alongside men’s knowledge. She hopes this will encourage other young Indigenous women to engage with and help with the curation and preservation of aspects of their own Indigenous cultures.

During their visit, the Wauja women provided vital information and context regarding Wauja traditions that added greatly to the utility and significance of the Smithsonian’s collection of Wauja artifacts. Future researchers of all backgrounds, including future generations of Wauja, will be able to analyze the impact of changing technologies, social dynamics, and craftsmanship when they review the videos created by the Wauja men in 2016 and Women in 2024.

Meanwhile, as this blog post is written, back in Brazil, in Wauja village schoolrooms, young men and women are given the homework assignment of choosing one of the short Recovering Voices videos from among the over 500 produced to transcribe the oral Wauja to written Wauja. Some of the advanced students also translate the written Wauja to Portuguese, making the material available to a wider audience. As an unexpected bonus, some of the students have reported that as they listen multiple times to each segment of the video in order to transcribe it faithfully, they end up memorizing the content without doing so on purpose. As the Wauja elders were chosen for their eloquence and mastery of traditional forms of Wauja speech, the young people are hearing their language spoken by the experts. Nowadays, of course, the style of speaking Wauja used by most young people reflects contact with Portuguese and with the rituals and expressions of social media, which is widely used. Thanks to the hundreds of precious Recovering Voices recordings of Wauja speech as spoken by learned elders, young Wauja can continue to learn the old ways as they learn the new.