Search

News from Recovering Voices

Welcoming the Wauja

By: Keren Yairi

11/01/2016

Deep in Brazil’s Amazon basin, the headwaters of the Xingu River have been home to the Wauja people for generations. Yet as the elder population dwindles and the youth increasingly assimilate, the Wauja language and the knowledge it expresses are becoming endangered. That is why a delegation of dedicated Wauja speakers recently made the strenuous six-day, 5,000 mile journey to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC to take part in the Recovering Voices Community Research Program. Their visit to the museum collections supported their community’s efforts to document the language while also providing unique opportunities for knowledge exchanges that will benefit additional endeavors.

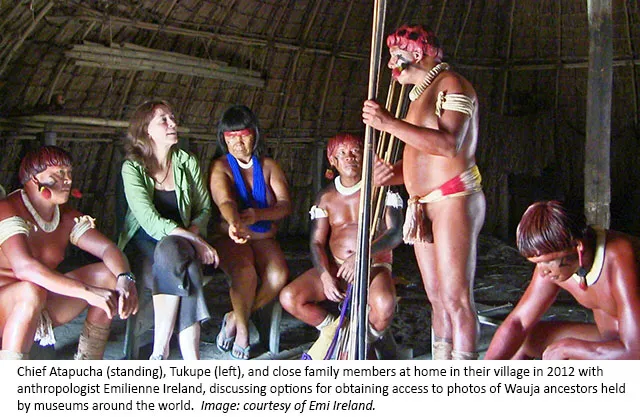

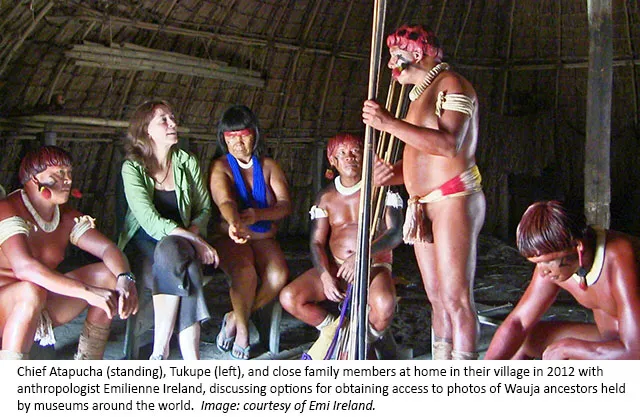

The participants included two prominent elders, Co-Chief Kuratu (from Ulupuene Village) and Chief Atapucha (from Piyulewene Village), both respected orators and authorities on the Wauja language. Atapucha’s nephew, Tukupe, rounded out the team through his closer connection to the community’s youth and his language preservation work with the younger generation of speakers. With these three representatives of various Wauja villages, the visit also became a means of solidifying inter-village relations. The team members were accompanied into Smithsonian collections by their two American collaborators and hosts, Emilienne Ireland and Phil Tajitsu Nash.

The group members visited a wide range of Smithsonian collections and archives from their home region, including historical film footage, cultural objects, and animal specimens. They provided explanations and commentary as they viewed each item, often sparking related stories or memories of disappearing traditions. This process elicited many Wauja vocabulary words and expressions that were once used in everyday conversation but are now rarely heard. The entire visit was video-recorded and photographed so that it can be used to produce materials for language and cultural preservation efforts back in the home communities and schools.

The videos will be transcribed and analyzed by Emilienne with Wauja collaborators, school teachers, and students, who will glean hundreds of words to add to Wauja-Portuguese and Wauja-English online dictionaries. Tukupe will work with other community members to transform the photographs, videos, and information collected into instructional materials, such as educational posters and an online Wauja museum. The Wauja are also hoping to eventually develop their own physical community museum or cultural center to teach their children as well as visitors about their way of life, in their own voice.

Starting in the Smithsonian’s Human Studies Film Archives (HSFA), the group viewed and annotated silent films shot in a Wauja village over 50 years ago. The films depict typical Wauja activities of the time, such as making feather headdresses and shell necklaces, extracting dyes and salt from plants, drawing water at the riverside, harvesting and processing manioc, and competing in wrestling matches. While some of these activities are still much the same, others are no longer performed, and young Wauja today do not know all the techniques involved or even the words to discuss them. The two elders on the visit are among the few remaining Wauja who once performed these very actions and can describe them in minute detail. Their commentary on the footage provides valuable vocabulary, historical context, and explanations that were missing from the silent films.

In addition, the two elders were able to identify virtually all of the individuals in the films. This was an emotional process for the chiefs, particularly watching footage of their own late fathers wrestling each other as youths. It is also meaningful to share this genealogical information with community members who have never seen images of some family members captured on camera. The HSFA is fond of saying it is in the “forever business,” and indeed these Wauja ancestors live on through the films. The elders also recognized individuals appearing at different ages in the various clips, even though the reels all carry the same production year. This discovery informed the archives staff that the films must have been recorded in different years. In turn, the Wauja were excited to learn from staff that additional, raw film footage as well as separate, original sound recordings might exist and could possibly be tracked down.

The team then visited masks, regalia, and other Wauja ceremonial items held in the NMNH Anthropology and NMAI collections. The elders, in particular, were enthusiastic to view the large palm-fiber masks that both their late fathers had participated in constructing. Since the Wauja regard masks as living beings, they were pleased to find these items properly kept and able to breathe, as spirits must do, and to see their other cultural heritage items well cared-for and securely stored. They were especially impressed by the protection of the sprinkler system, and Co-Chief Kuratu delivered a heartfelt oration of gratitude to the security guards for watching over the Wauja ancestors. In turn, one of the elders showed collections staff how to more appropriately display the shell necklaces.

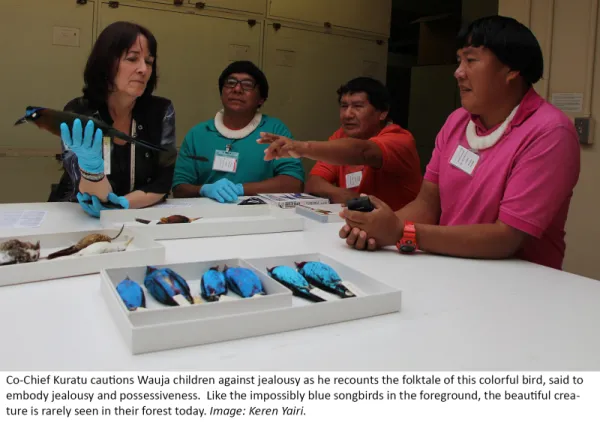

Visits to the NMNH Departments of Ornithology (birds), Entomology (bugs), Ichthyology (fish), Invertebrate Zoology (snails), and Herpetology (reptiles and amphibians) allowed the group to examine a wide variety of animal specimens from the Xingu region. Smithsonian curators located specimens of the same kinds of fish that Kuratu and his friends collected as young boys, while snail experts helped the Wauja link species they recognized to their scientific names. The trio offered eloquent words of appreciation to the scientists for sharing information about the collections, especially to Dr. Oliver Flint, Curator Emeritus in Entomology. Respectfully addressing the senior researcher as “Grandfather,” they explained that in the Wauja language, this term of deference honors an elder’s wisdom.

As they viewed the colorful toucans, brilliant butterflies, scaly snakes, and tiny hummingbirds, the Wauja demonstrated bird calls, recalled strategies for attracting fauna, and described how animals were traditionally used. They also shared references to the creatures in their songs, poems, prayers, stories, and expressions. For example, a jealous person is compared to the multi-colored irumehe bird, whose beautiful tail feathers were said to be plucked out as punishment for his unreasonable displays of jealousy toward his wives. And some girls, including Chief Atapucha’s own niece, are named after the lovely Periru moth, grandmother of the sun.

The joyful musings were tinged with sadness, however, as many of the species viewed in the museum collections are dying out or have permanently migrated out of Wauja lands due to environmental change. For example, villagers sometimes resort to using dyed chicken feathers for ceremonies because the colorful native birds are rarely seen anymore. Wauja youth today also spend more time in the classroom than the forest and are not gaining the extensive firsthand knowledge of wildlife held by their fore-bearers. As part of the last generation with intimate knowledge of the rainforest, the elders were able to provide critical information about these animals before their knowledge, and indeed the wildlife itself, disappears.

The trade of ideas continued as the Wauja remained in Washington, DC after their collections visits. The group presented a short documentary on climate change in their region to the American Indian Student Union and the Native American Studies Program at the University of Maryland, engaging in discussion with the students and leading them in traditional Wauja dances. The group also met with a Zuni delegation from New Mexico, who were in DC on their own Recovering Voices Community Visit, as well as with members of the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma, who were in DC to plan the 2017 National Breath of Life Archival Institute for Indigenous Languages. Discovering common cultural practices and historical experiences, the groups shared thoughts on language revitalization efforts in their respective communities. As the Wauja make the long journey back home in Brazil, they will look back on many meaningful experiences and forward to the next steps of the momentous task ahead.