Search

News from Recovering Voices

Unravelling P’urhépecha Textiles with Uekorheni AC

By: Mackenzie Wright

10/21/2024

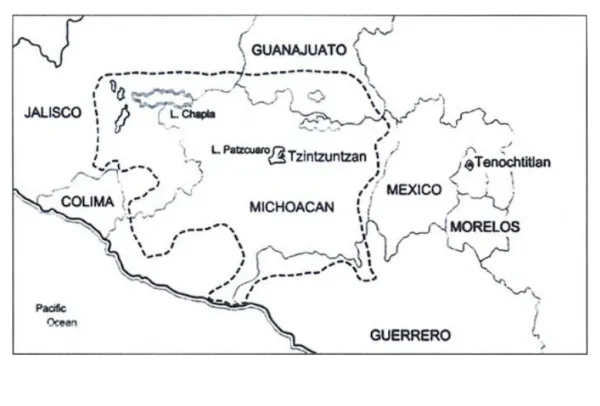

Towards the end of September, three members of the P’urhépecha community, Huecorio specifically, traditionally located throughout present-day Michoacán, Jalisco, Guanajuato, and Colima, visited Washington, D.C. from September 9th to 13th, 2024. Within the P’urhépecha ancestral territory, Huecorio is located on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro in Central Michoacán. The Lake Pátzcuaro area is one of the four sub-regions of the P’urhépecha territory where a majority of the P’urhépecha population is currently located—this sub-region is called Japundarhu (Japunda in P’urhepecha means lake).

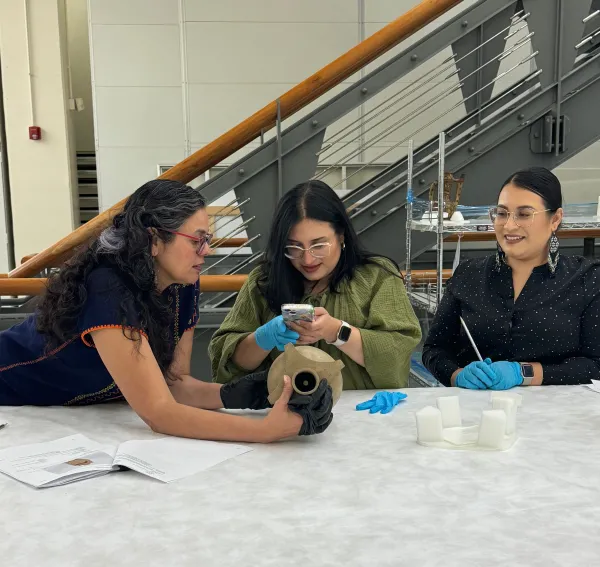

The group consisted of María Gutiérrez de Jesús, Sandra Gutiérrez de Jesús, and Tania Domínguez Gallegos from Uekorheni AC, working with collaborators Gwyneira Isaac, Cali Martin, Laura Sharp, and Mackenzie Wright from the NMNH Recovering Voices department and NMAI collections staff. The focus of this visit is to study textile patterns, embroidery, and craftsmanship of P’urhépecha collections held at NMAI and relevant archives at the NAA to disseminate knowledge surrounding traditional textiles to community members from a P’urhépecha perspective. This visit supplements an ongoing project of theirs, titled “Sïrikupani Tsánharhikuecha (Weaving Dreams): Los textiles tradicionales del Pueblo P’urhépecha como memoria histórica colectiva (P’urhépecha traditional textiles as historical and collective memory).” As part of this project, they also engage with an embroidery circle comprised of P’urhépecha women from their community that shares knowledge and teaches younger generations the craft of traditional embroidery.

María, Sandra, and Tania are part of Uekorheni AC, a collective of P’urhépecha individuals dedicated to preserving traditional P’urhépecha arts, languages, cultures and knowledges in the face of colonialism, racism, and repressive actions aimed to diminish indigenous craft. They founded a women-led, community-based radio show, Radio Uekorheni, in their community (Huecorio) that emerged in 2017 to disseminate knowledge and organize workshops to encourage community collaboration across the many P’urhépecha communities of Michoacán. María serves as the project lead, Sandra as the project research coordinator, and Tania as the media coordinator. Each brings a unique perspective in understanding cultural shifts in the design and iconography of textiles collected across the 1900s housed within NMAI collections.

From sashes and skirts to ponchos and huanengos, these textiles showed a wide variety of craftsmanship, with many pieces displaying beautiful woven and embroidered patterns of florals and geometric designs. The participants often commented on the attention to detail in embroidery, identifying the difference between artisan and non-artisan textiles depending on the neatness of the backside of the embroidery—the more tangled it was the more likely it was not done by an artisan, or by someone who is still practicing and/or just starting. Many of these textiles have not been seen in the community since the 1980s, but there is an obvious record because of paintings done by Tania’s husband, artist Esteban Silva, documenting traditional regalia across P’urhépecha communities.

The textiles depicted in the NAA photographs and seen in NMAI collections were older textiles based on the dates of acquisition/donation to the Smithsonian. Based on this, while some of the pieces belong to P’urhépecha communities, some pieces were most likely made in other communities for sale and marketed as “Indigenous” clothing—possibly made or purchased for school cultural events. Even though the group discussed and could not necessarily confirm this, they came to the consensus that these more “generic” textile pieces seemed to be made for general sale.

In comparing the two skirts below, they noticed that the one on the right has a checkered pattern, a short green trim, and an added green hem on the bottom—not a traditional pattern/design you would see today in P’urhépecha communities. The left skirt more similarly resembles what is worn today, a plain red skirt with a thick green satin trim with plenty of space to add sashes and belts in that area. Such skirts are traditionally worn by unmarried women to signify their status and are usually seen on younger girls, however, women today are re-signifying traditional regalia by incorporating their own visions pertaining to their clothing. However, even the more traditional skirt has its differences with wool being used as the primary fabric.

“We appreciated it seeing this item. In our community, Huecorio, wool is a material that is no longer worn in skirts, but we have stories of our grandmothers wearing these skirts that in our language we call sïrijtakua.” (María)

The group theorized that wool was used when the temperatures were colder in the area, when the lake was fuller, and communities were not as affected by climate change as many groups are today. In recent decades the traditional P’urhépecha territory has been deeply impacted by climate change, and environmental destruction that has been induced by agri-businesses. The rapid expansion of agro-industries such as avocado production has led to significant land-use transformations. This is mainly reflected in the alarming rates of deforestation and scarcity of water reserves. The entry of Mexico into the global markets through the adoption of neoliberal policy (1990s)—a economic and governance model centered around the privatization of the commons (public sectors and natural resources that are not traditionally seen by Indigenous communities as commodities (the earth, water, rivers, etc.) provoked important changes in Indigenous communities, such as the privatization of collective-held lands, leading to the expansion of agro-export industries into the countryside. The adoption of the North American Free Trade Agreement between Mexico, Canada and the United States in 1994 paved the way for relatively new industries, such as avocado production, to expand. This context framed land acquisition practices that ended up destroying forested areas to establish avocado orchards as that became a profitable business.

All this at the expense of Indigenous lands and communities. An avocado tree consumes around one thousand liters of water/month. The establishment of avocado orchards in the area, endorsed by municipal governments and organized crime, have made these environmental transformations a complex issue to address. The extensive forests that once stood in our region have gradually disappeared. All this to say that these change in the environment are human induced, and this has also affected other aspects in the P’urhépecha community, such as migration, language loss, access to natural medicine and raw materials to produce traditional crafts, and of course, transformations in traditional regalia (María, personal communication).

As such, modern clothing typically uses more polyester blends as they are easily accessible and cheaper and help adapt to a more temperate climate. In addition, there are communities who engage in bartering when it comes to clothing. For example, some women will trade their expensive pieces of clothing to other women in different communities to wear for celebration—the barter system has been in existence since pre-colonial times in the Mesoamerican region where the P’urhépecha belong. Other adaptive garments are seen today, with many modern huanengos incorporating cultural influences such as Disney characters and animals, mostly for young kids, in addition to the traditional flower/geometric patterns. Many of these innovations are from broader cultural influences; most families have family members in the US and US popular culture is imminent.

With the efficiency and hard work of the team, all the textiles they had originally requested were examined by the end of the first day, leaving plenty of time for review and looking into more P’urhépecha belongings such as ceramics and wooden masks.

In looking at the ceramics, the group wanted to compare iconographies shown on the textiles to those on the ceramics. Many of the ceramics did indeed show similar designs traditional to the P’urhépecha, but some were flagged as a non-P’urhépecha and made note of by Cali, an NMAI collections staff, to edit the museum catalog information and reflect a more accurate label. One such item perplexed the group (depicted above), with its modern/geometrical appearance and hole at the bottom of the vessel (clearly not used for water). Although they did not recognize it as P’urhépecha, pictures were sent to members of the community and artisan potters to verify and gather more information before community association is changed.

“There were a couple pieces that had the signature of the family who made the pottery in one of the communities on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro – Tzintzuntzan. We took note of that and are planning to go to Tzintzuntzan and look for the family to ask about the pieces.” (María)

Museum Tip: Although museums try their best to provide accurate information, catalog information can be wrong! If you have any concerns, comments, or additional information that pops up while browsing online or physical collections, please contact museum staff so they can be made aware of any inaccuracies and/or update the records.

During their visit, the group also visited the NMNH collections, looking at a variety of face masks, throwing sticks (atlatl), and spears, and the NAA to see photographs documenting P’urhépecha textiles and women's traditional wear. The throwing sticks and spears drew strong interest because many of those in their community (especially the younger generations) grew up with stories about duck hunting practices—some even talk about rituals made prior to the hunt—but are something that some had never seen in person. They also found masks that take the form of a duck when looking at the mask collection, but are unsure if the masks, which were old, were used as part of these rituals, or if they were totally unrelated. Relating this to the previous conversation on the environmental crisis in the P’urhépecha region, duck hunting is a practice that does not happen anymore (María, personal communication).

While visiting the masks, it was also noted that a majority of the masks in collections are older and not typically seen in communities anymore, dating closer to the early 1900s. Current masks are smaller, use wood in place of actual cow/goat horns, and take on more humanistic features whereas old masks reflect animal features, have real fur, horns, and horsehair (and teeth), and can be heavier due to their size and the solid wood structure.

“One of the pieces that caught our attention was a set that came with a mask with animal hair, embroidered shorts, and sable. We discussed that this set was in fact from a traditional dance. Also, the wooden drum (kuiringua) that we saw was very interesting. To us, items such as these raised discussions about cultural and spiritual regalia, thus thinking about ways in which as Indigenous communities in Latin America we could engage in repatriation/rematriation of “artifacts” to our communities.” (María)

With all this newfound knowledge, Uekorheni AC plans to install a new photo exhibit in their community to display the 28 traditional regalia paintings from graphic artist and painter Esteban Silva alongside the information and photos gathered during this visit. The intent is to inspire textile and artistry revitalization in patterns, materials, and iconography that has been lost and/or changed over generations. The group generously donated a collection of 8x10 prints of the original paintings to be included in the existing P’urhépecha prints at the NAA.

Further initiatives to disseminate the knowledge learned include embroidery workshops and radio spots covering topics of traditional textiles to better incorporate the larger P’urhépecha community in the learning and reflection process. And, as a community-based project that works on initiatives focused on the P’urhépecha language, they also plan on working with P’urhépecha language activists in their region to find more information about the pieces they looked at in the Smithsonian collections.

For more information and updates about Uekorheni AC, check out their radio station, Radio Uekorheni, and Facebook. Also take a look at Tania’s art group, Taller de Papel y Gráfica DeLirio, for information about locally produced and sourced aquatic lily and maize paper products, and https://lenguasoriginarias.com/curso-de-purepecha/ to learn more about the P’urhépecha language!