Search

News from Recovering Voices

Rediscovering Marshallese Plaited Mats

05/13/2019

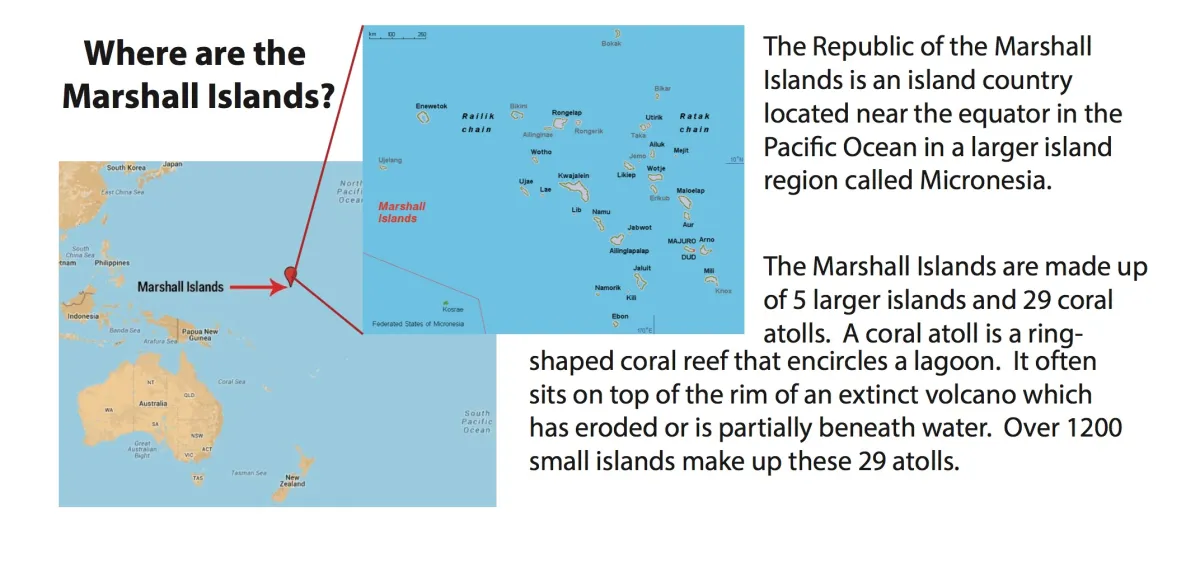

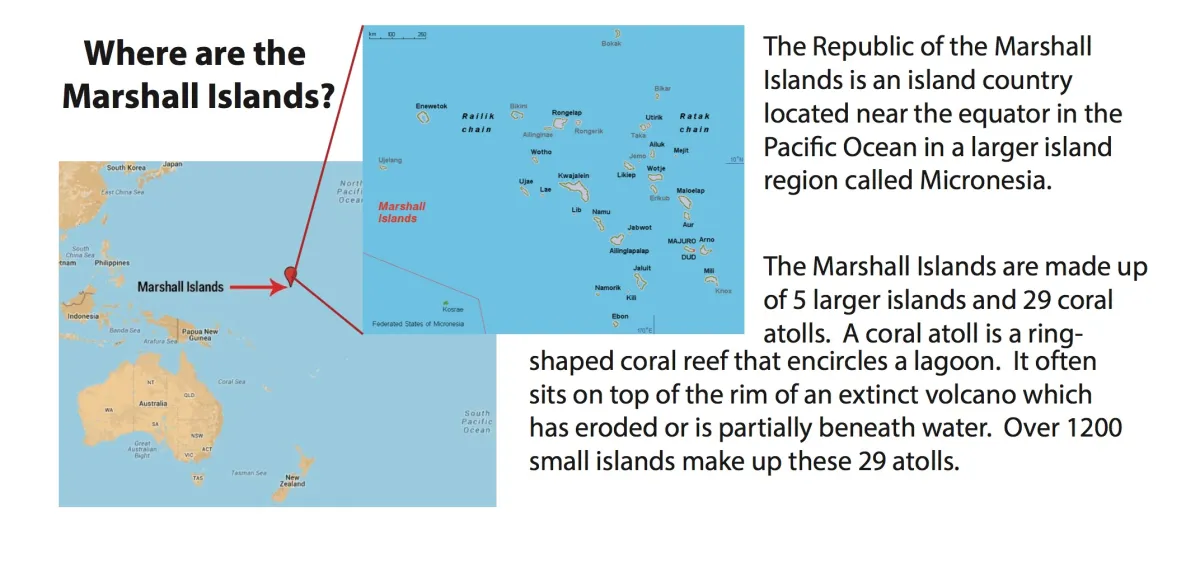

From April 20 to May 6, 2018, a group of weavers from the Republic of the Marshall Islands took part in a two-week Recovering Voices Community Research Program visit. The weavers, Susan Jieta and Rosie Helmorey, were assisted by project coordinator Aileen Sefeti, collaborator Dr. Ingrid Ahlgren, and the RV Community Research Manager, Judith Andrews as they studied historic plaited mats held by the Department of Anthropology at NMNH. These finely plaited mats, called jaki-ed or nieded in Marshallese, were worn in the past by people of the Marshall Islands.

Susan, a master weaver, and Rosie, a now-experienced apprentice, are part of the Jaki-Ed Revival Program at the University of the South Pacific in Majuro, the capitol of the Marshall Islands. Aileen is the Program’s project coordinator. Beginning in 2006 at the University of the South Pacific (USP) Majuro campus, traditional leader Maria Kabua Fowler and Dr. Irene Taafaki, Director of the USP Majuro Campus, founded a program focused on reviving the art of weaving jaki-ed. The program has reintroduced ‘lost’ or forgotten designs and patterns, trains new weavers through an apprentice program and workshops. Using museum collections of early Marshallese mats as a way of inspiring and informing motif, design choices, and techniques a new generation of weavers has emerged.

These finely woven mats from the Marshall Islands were most commonly worn in sets of two by women, held in place by long belts, wrapped around their waists. Similar mats, with intricate symbolic designs, were also worn by men as loin cloths, or by chiefs during special events. Traditionally, the plaiting – a type of weaving - of these mats and other items (fans, sleeping mats, sails, baskets, etc.) was prominent in every aspect of Marshallese daily life. While the Marshallese people have continued to make other woven materials, they stopped making these special clothing mats in the early 1900s when they began to wear western-style clothes like dresses, pants, and shirts.

Access to historic collections held in museums is vital to the revival of the jaki-ed weaving tradition. The mat collection held by the NMNH Anthropology Department is a valuable resource because it includes dozens of clothing and ceremonial mats in various stages of production, as well as tools and the raw materials used in their making. Most significant of these historic materials were collected by Charles H. Townsend and H.F. Moore, during the US Fish Commission’s Albatross 1899-1900 Pacific Expedition. This collection even includes two dreka in niin, important pounders made of giant clamshell that are used in the processing of pandanus leaves for weaving. The weavers were excited, but surprised to see these, knowing they would have been passed as heritage heirlooms down the family line but in this case were transferred to foreigners. (Note: The Albatross was the first large purpose-built marine research vessel in the United States).

During the research visit Susan, Rosie, Aileen and Ingrid discussed the construction, designs, and materials of the historic mats. Some of the mats were damaged through the years, whether by breaking on a fold, by vermin nibbling, or some other damage prior to arriving at the museum. (Sidenote: Museum Insider tip. Store textiles flat or rolled. A weaving made in a warm, humid place will break easily when dried out, especially if it has been stored folded, it will break on the fold line.) At the time of the visit, conservator Rebecca Summerour was finishing up her work conserving and stabilizing the most fragile of the damaged.

The research visit allowed for the perfect opportunity for conservator and weaver to confer. The weavers were intrigued by the inclusion of foreign materials – like rice papers common in conservation work – used to repair the historic mats, instead of the traditional pandanus plant fibers. This led to a healthy discussion about the priority that the western science of conservation holds, to make repairs that stabilize the textile so the life history of the object can be read in its repairs. This contrasts with traditional ideas that Susan shared regarding the importance of sourced materials as well as the significance in giving and presenting high quality mats to their recipients. She (the unnamed weaver) would never have wanted someone to see a mat of hers blemished, nor would she present a mat to its intended recipient, which would be an insult and could even bestow bad luck upon them. Susan’s initial response as a weaver to seeing a blemished or unraveling jaki-ed would be to repair it with traditional sourced materials so you could not tell it had been damaged. After this dialogue, both sides agreed that mats in the museum collection are important not only because of the designs and motifs woven into them, but also the stories they can tell about the lives they’ve had after leaving the Marshall Islands.

During their research, the Marshallese weavers rediscovered designs, motifs, and techniques in the historic mats that they were not familiar with. They ended their visit to collections excited to go home and try out these patterns and experiment with different approaches. The Smithsonian and our conservation team were left with a better understanding of traditional Marshallese weaving knowledge for the benefit of future weavers and researchers.