Search

News from Recovering Voices

Interning with RV: Capturing the Natural World with the Person at NMNH

By: Jab'ellalih Ixmatá Schaaff

10/28/2024

Hi, I’m B’ella! This summer, I interned for Recovering Voices (RV) and had the pleasure of assisting with Community Research, helping with office tasks and catching glimpses of what a career in a museum could look like. Interestingly, within the first few days of starting my internship, I sat in on an anthropology department meeting with the chair, Joshua Bell, who enthusiastically reiterated that anthropology has a place at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), and natural history museums more widely. This question does anthropology belong at Natural History? is one I encountered both explicitly and implicitly during my two months at Recovering Voices. It is difficult to answer, yet it also characterized my time this summer.

I am currently a senior at Wellesley College, majoring in Cognitive and Linguistic Sciences. My personal research interests lie with the study of Mayan languages, specifically my mother’s, K’ichee’. I grew up in a household where Indigenous identity, culture and practice were a part of my every day. However, the language—something I never fully grasped, yet holds my personal interest—was something I could cultivate into a passion. While I do not speak K’ichee’, I have made it a mission to study heritage language and its speakers, especially with communities in diaspora.

I first heard of Recovering Voices from Gabriela Pérez Báez, who worked at the National Museum of Natural History and RV years ago. Two summers ago, I participated in a program at the University of Oregon which put Indigenous language at the forefront, and I was fortunate enough to make this connection through Gabriela. Admittedly, I was under the impression that the bulk would be related to language revitalization and language rights. While Recovering Voices emphasizes the significance of language for communities and research, I was unfamiliar with the methodology employed to encourage linguistic confidence. Language is a key component to the communication of tradition: this can be oral history or commonplace conversation. In the context of working with a museum, however, language intersects with the material.

This was made most evident to me during the two-week long Wauja visit RV hosted in July through its Community Research Program. The Wauja project particularly involved videotaping conversations around Wauja material culture, following the conversation of three Wauja women from the Amazon River basin who are also Wauja speakers. Not every Community Research Group is obligated to record their research, as each group has its own approach to what they need or want from their interaction with the collection. In this case, we recorded the Wauja women talking about the construction of ceramics and baskets and how they reflected the natural world. This approach targeted two issues in the Wauja community: loss of language and loss of traditional knowledge. These women explained in Wauja, an endangered language, how the ceramics and baskets were created and how they were used. Naturally, conversations and personal anecdotes arose. Pere, one of the Wauja women, has an incredibly active imagination and is also a storyteller in her village. Even though I could not understand her language, she had an infectious smile and laugh that offset the apprehension about coordinating the research and its visit.

Going backwards a bit to before the visit, there was great worry that the Wauja women would not make it to D.C. at all. Through a series of unfortunate events and obstacles, the weeks leading up to the scheduled (and then re-scheduled) visit were fraught, to say the least. Nobody was at fault, thus the best we could do was hold our breath and cross our fingers that everything would work out. During this time, I was occupied with writing an information packet for future research visits, assisting in office tasks, and getting to know the collection at the Museum Support Center (MSC).

The Wauja visit primarily took place at MSC and I am glad to have had some time getting to know the complex before their arrival. My first introduction to MSC was during my first week at RV where I was fortunate enough to stand-in during a Coast Salish visit. They were looking into the woolly dog specimen that is held at MSC. I had heard of the woolly dog but was completely surprised to discover the scientific study involved with the dog. For context, the woolly dog has gone extinct, but its legacy is one of artistry and environment. The Coast Salish used woolly dog fur fibers for making blankets and cloaks, and, most excitingly, there is one preserved woolly dog at MSC named Mutton, who we caught a glimpse of. Again, we reached a junction in which the “traditional sciences” met with the science of anthropology—a redundancy, I am aware. Mutton had been studied in a genetics lab and researchers at the Smithsonian were able to find his diet, his closest genetic relative and impressions into Mutton’s lifestyle, and by extension, the lifestyles of the Indigenous people who had been caring for him.

This emphasis on how Indigenous people interact with their natural environment was continued during the Summer Institute of Museum Anthropolgoy (SIMA). I was able to sit in on various lectures and activities dedicated to teaching post-grad researchers how to conduct research in a museum and how to develop their research ideas. During this program, the question, does anthropology belong at Natural History? was posed several times. Indeed, I think those who have made a career in anthropology at NMNH would be very supportive of maintaining the department, with convictions that go beyond stable employment. There is an inherent humanity to the study of anything in the natural world: rocks, bones, birds, bugs, and more are studied for a greater understanding of our world and our place in it. The anthropological aspect of natural history is particularly illuminated when you witness the testimony of those who engage with what we only gawk at from behind the glass.

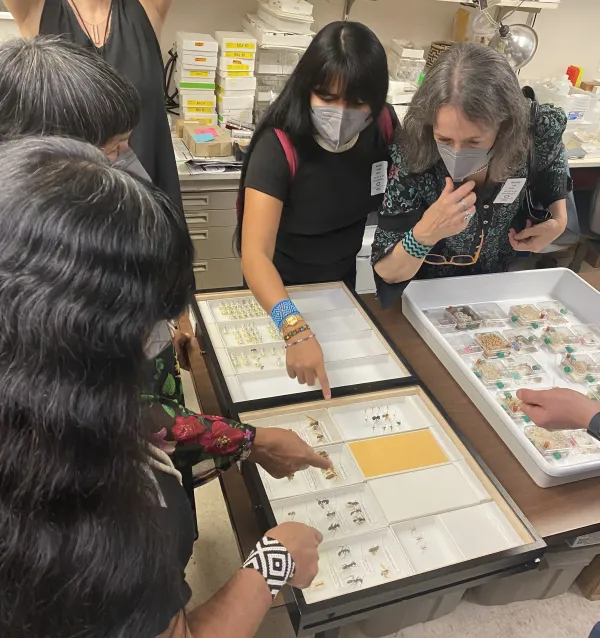

Returning to the Wauja visit, their second week was spent in the Natural History Building. This portion of the visit was dedicated to visiting species that are found in the Amazon and would have been familiar to the Wauja women. We visited the entomology and bird departments (two undeniable Natural History! departments) and watched as the women discussed the critters they found familiar.

I will admit that on my part, it was a little unsettling to see a myriad of colorful birds laid out on a table in a dimly lit research collection. It seemed contradictory to the purpose of a bird; they’re supposed to be loud—in color and in voice—and fly or run, not lie motionless so far from their original homes. Immediately, the Wauja women huddled and pointed excitedly at the bird specimens. Except they were not specimens anymore, they were enlivened by the thrilled screeches, caws and trills coming from the women. This is how they identify the birds. Binomial nomenclature is meaningless compared to the lived knowledge these women have. They grew up with these birds in their backyards. Their songs are the soundtrack to their everyday.

My answer to whether anthropology belongs at a natural history museum is informed by what I have seen. Language, culture, spirituality, the intangible nature of identity all undoubtedly exist in the context of the natural world. And indeed, we as humans are also a part of the natural world. For this reason, I believe that a true natural history museum is only faithful to the study of Natural History when it involves the study of people, too. I do not mean to spur debate, but even I was initially surprised by the inclusion of an anthropology department in the museum, yet now, I am a supporter of it.

As my time at Recovering Voices has come to an end, I’d like to thank everyone in the anthropology department for welcoming me. My suitcase was packed with books I picked up from staff and I made incredible connections with people in or around my field of study. I’d also like to thank the communities I worked with or whose material culture I interacted with. My time at Natural History exposed me to just a fraction of the art, tools, ceremony and life that are housed by the museum. Most importantly, I’d like to thank Laura Sharp, my supervisor, who definitely took on another job by guiding and watching over me this summer. I believe there is a possible career for myself in a museum, and I hope that anthropology at NMNH continues to bridge the divide between the sensory and the lived.