Search

News from Recovering Voices

Chance Meetings – Biliirr performance at NMNH, Smithsonian

By: Tierney Brown and Joshua A. Bell

04/15/2016

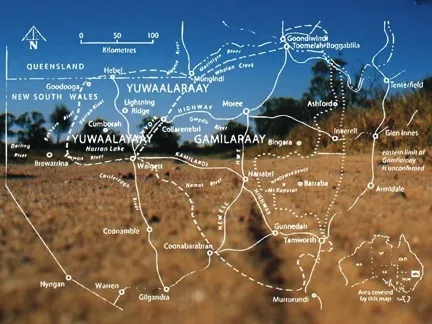

On a bright afternoon in March, songs in the Yuwaalaraay language welcomed visitors to the National Museum of Natural History. Those who entered Q?rius were greeted by Bilirr (Yuwaalarary for black cockatoo, Calyptorhynchus banksii), a performance group of three sisters who use music to explore language revitalization and their Yuwaalaraay traditions from inland eastern Australia. Standing in front of a large image of the Great Barrier Reef, the sisters – Nardi Simpson, Jilda Andrews and Lucy Simpson sang songs that celebrated their childhood, their connection to the land, the rich opals of their country and their Aboriginal heritage. Nardi, the eldest, is a musician and songwriter starting projects such as Stiff Gins, Freshwater, and the Spirit of Things Collective. Jilda Andrews is a PhD candidate in Anthropology and Interdisciplinary Cross-Cultural Research at the Australian National University where her thesis is on “Adding value to ethnographic collections in Australian museums.” She also works for the National Museum of Australia designing outreach events targeted at non-traditional audiences. Lucy Simpson, the youngest of the sisters is an artist and designer with her own line of handmade Yuwaalaraay inspired textiles and pieces, Gaawaa Miyay, “River Daughter.” The group came to DC as part of a larger collections research tour they were doing with Dr. Louise Hamby of the Australian National University, who has worked on various collections inspired collaborative projects. As Lucy elaborated in the seminar that followed their musical performance, her work and indeed that of her sisters is marked by a series of “chance meetings” in her words, with elders and objects. Indeed, for those that came in contact with them their performance and work in the museum was another chance meeting that lies at the heart of what Recovering Voice’s core mission to connect communities to collections.

Prior to their performance, the group spent a day at the Museum Support Center where Anthropology collections are housed in Maryland looking at objects obtained from Aboriginal Australian communities. In particular the sisters were inspired by their encounter with the oldest known Possum Skin Cloak (E5803-0) from Australia in a museum collection. The soft warm fur of 23 brush tail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula) and one great grey kangaroo (Macropus canguru) stitched together seamlessly composes the enveloping interior surface of the cloak, the leather side faces out with intricately incised patterns cut into the hides, zigzagging across one belly and wrapping into concentric diamonds cutting across the next, with several stylized human figures spread across the tableau. Horatio Hale, the ethnologist and philologist of the US Exploring Expedition (1838-1842), collected the cloak in 1839 from the Hunter River which runs through New South Wales. It’s identification in the catalog as a “Worowan” indicates it is likely of Wonnarua, Awabakal, or Worimi origin.

Some Aboriginal source community researchers have collaborated with the National Museum of Australia to revive cloak-making knowledge and practice, and other groups have expressed interest in working with these objects to revitalize language, cultural practice, and art forms. Nardi Simpson described in her presentation the next day how the Yuwaalaraay once made possum skin cloaks too, how they were cumulative objects that were built up as the person grew: a single skin swaddling a newborn, growing as they did, serving as blanket, cushion, instrument, and shelter from rain or cold, until it finally covered the person as their burial shroud. (Wilkes Account Vol. 2, page 196). Other groups in the region record the cloaks as heirloom objects that would be passed through generations, and across the region people knew them as a common but treasured item against the climate.

But the group had equally powerful chance meetings with more humble objects such as a “twined wallet of grass” (E203743) and two reed necklaces (E5802). The former was a gift from the then US Consul F.W. Goding in 1899, while the latter was obtained during the US Exploring Expedition in 1839 from Wellington Valley, New South Wales. Each was a testament to the care and skill with which communities crafted their objects, each was also an evocation to think about new designs and work inspired by this material heritage.

On Thursday, March 24, 2016 the sisters performed as Biliirr in Q?rius, the interactive education space for the Natural History Museum, followed by a discussion of their visit and ongoing projects in the Q?rius theatre. Biliir’s songs relate specific scenes of life as freshwater people: the memories and anticipation of spending summers in the river, finding opals in the dusty rocks, and negotiating public displays of affection, but their songs are utterly relatable to their audience. Biliirr as a project also seeks to explore Yuwaalaraay language expression and lived culture, some of the songs are completely in Yuwaalaraay, or weave together Yuwaalaraay and English in strong beats on clap sticks and the harmonies of the sisters’ voices. For their last song they invited audience members up, especially kids, to participate with clapsticks and follow along with the dance gestures and sounds of naming the local wildlife in Yuwaalaraay.

Following the performance the group presented about their own work and connection to museum collections. The sister’s moving narratives of creative drive and connection to historical objects and cultural patterns encountered in museum spaces energized them to contribute new music, design, and scholarship as they delve into their own vibrant heritage and work to make the voices in the collections heard, and draw out other stories from communities to create more dialogs of revitalized and diverse storytelling. Lucy’s designs incorporate myths and stories in patterns recognizable to members of different communities, and serve, as she related, as conversation starters to share culture and meaning through beautiful textiles and reflective works of art. While Nardi’s music introduces more people to the project of language revival and indigenous cultural movements and allows her to create a dialogue with voices from the past. And Jilda’s research following Catherine Langloh Parker has dovetailed with her studies of collections and communities in the museum context to further engage with the living presence of culture and objects and how collaboration and progressive understandings of dynamic culture. The sister’s work brought up a lot of great discussion with the audience, and was a wonderful reminder of the power of chance meetings with objects and people by which the work of Recovering Voices thrives.