Search

News from Recovering Voices

Documenting Smithsonian Institution canoe collections from the Pacific Islands

By: Dr Chris Urwin, Research Fellow at Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, Monash University (Australia)

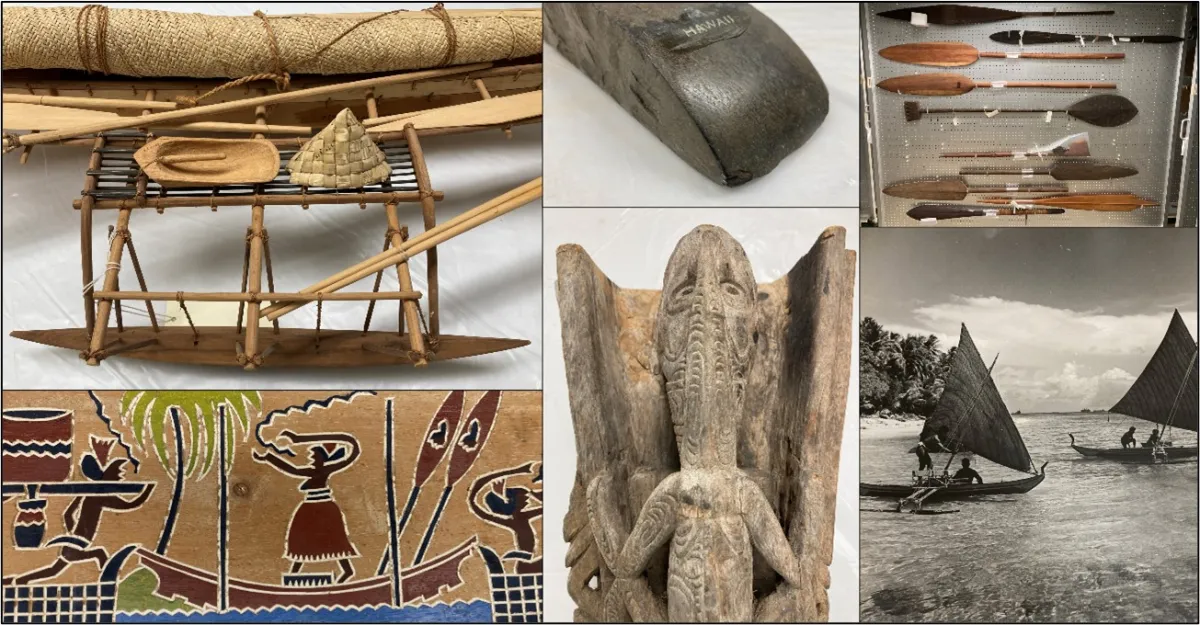

This year, as a Peter Buck Postdoctoral Fellow I’ve been working to document more than 300 canoe-related objects from the Pacific Islands cared for by the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). I surveyed collector fieldnotes, letters, and photographs in the National Anthropological Archive (NAA), along with footage of canoe-building and use in the Human Studies Film Archive. The aim of the project is to draw out stories of Indigenous voyaging and American collecting in the region, to map the provenance of the canoes, and to make this knowledge accessible for Oceanic canoe makers, voyagers, and communities.

Museum collections of canoes have long played an important role in Indigenous voyaging revitalization projects. In the early 1970s, Herb Kawainui Kāne – the Hawaiian founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society – based early designs for the seagoing canoe Hōkūle‘a on depictions of Polynesian canoes sent to him by various museums. In 1976, he captained the vessel on its successful voyage from to Hawaiʻi to Tahiti. Famed navigator Mau Piailug of Satawal Island (Yap State, Federated States of Micronesia; FSM) guided the vessel based on his observations of the stars, sun, moon, and ocean swells. Aspects of his navigational skill and knowledge, and his work with the Polynesian Voyaging Society were documented in the 1983 film The Navigators: Pathfinders of the Pacific, a copy of which is held in the Human Studies Film Archive (as well as extensive outtakes). Piailug himself donated a coil of rope and an outrigger canoe model to the Smithsonian in 2000.

More recently, Hawaiian and Māori canoe carvers came together for The Wa’a Project in 2018 to study a remarkable outrigger canoe donated to the museum by Queen Kapi’olani of the Kingdom of Hawai’i in 1887. The project was coordinated by Joshua A. Bell (Curator of Globalization) and Kālewa Correa (Curator of Hawai’i and the Pacific at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center) and funded by the Recovering Voices Community Research Program. This project flowed from an earlier project in 2017, for which Māori carvers Jacob Tautari, James Eruera, and James Rickard finished the carving of a contemporary waka (canoe) named Tuia te here tangata waka in the Q?rius science education center of the NMNH.

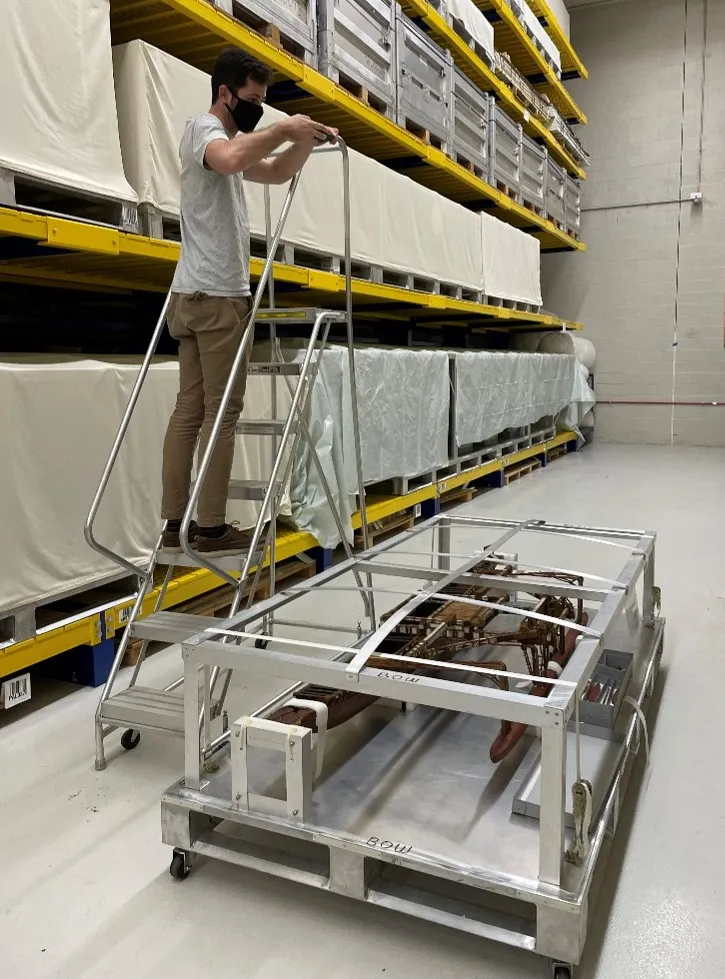

The NMNH collections include nine full-sized canoes, along with numerous model canoes, paddles, ornaments (e.g., carved figureheads), carving and building tools, navigation charts and items used in navigation magic (e.g., hos charms from the Micronesian islands of Puluwat and Woleai). These ‘things’ are important historical records of canoe construction and use through time. For example, the Smithsonian Institution cares for 15 ‘stick charts’ from the Marshall Islands in Micronesia. Most of the charts were made from the roots of pandanus plants and marine shells, and they were used by Marshallese navigators to learn ocean wave patterns in relation to land so they could sail between distant islands. Items like these materialize generations of Indigenous seafaring knowledge.

Collectively these objects were obtained from 1838 to 2017. Many of the early collections were acquired through US Government-sponsored scientific voyages, such as those of the US Exploring Expedition (1838–1842) and the US Fish Commission (1899–1900). The collection is diverse, with items originating from 112 different named locations (some of these are specific villages, while others are given as islands or regions). Many of the items were collected in Micronesia, including the Marshall Islands and the states of Chuuk and Pohnpei (Federated States of Micronesia). There are also substantial collections from Hawaiʻi and New Guinea. For the most part, these patterns of collecting reflect the history and geographic spread of US colonialism in the Pacific.

My research on the canoe-related objects involved documenting and photographing each item. Seen close-up, the items provided crucial clues and new details about their life-histories (how they were made, used, and stored over time). Some of the canoe hulls were damaged from collisions or being dragged across reefs. Some items bore the signatures or marks of their Indigenous makers. For other objects, close inspection yielded new information on the types of wood used for carving, the plant materials used for lashing, materials used for caulking, and pigments used for decoration. Many of the model canoe hulls had been made from multiple pieces (or planks) of wood attached using wooden pegs and lashed together with coconut sennit (made from braided strands of coconut husk fiber). Some items had been repaired by collectors or museum workers with wire, screws, or glue.

Documents and photographs in the NAA shed light on the networks of Indigenous makers, intermediaries, and American collectors who assembled the collection. For example, Robert W. Grant acquired seven model canoes from Kiribati and Tuvalu. He collected the items in 1942–1943 during the Pacific War, as he moved from island to island with the aerial reconnaissance division of the US Air Force. His papers and photographs in the NAA show that the items were used either as toys or household ornaments, or in some cases were replicas of contemporary watercraft requested by Grant. In Kiribati, he acquired each item by visiting the maker several times, first to establish a relationship, then to commission the item and check in on their progress. In Tuvalu, his collecting was enabled by an Indigenous colleague called Teinilowlow, who was employed as a ‘mess attendant’. Archival connections like these can help us trace the makers who crafted each of the canoe-related things at the NMNH.

Alongside documentary archives, the film collections of the HSFA contain unique depictions of canoe building. From 1976 to 1982, some 150,000 feet of film was shot in Micronesia by filmmakers Mathias Maradol, Ed McLain, Steven Schecter, and Scott Williams for the Smithsonian’s National Anthropological Film Center. Film recordings were made on the atolls of Woleai and Ifalik (Yap State, FSM), and Puluwat (Chuuk State, FSM), and they document many hours of everyday activities in and around canoes and canoe houses (beachside shelters where canoes were kept). They also show sailing canoes being fitted out for long-distance voyages, and the ceremonies and feasts which took place in relation to inter-island travel. Children can be seen playing on and paddling small canoes, along with men socializing in canoe houses. Moments of inter-generational knowledge transfer are depicted, including elders teaching younger men how to twine sennit cord and assemble canoes from carved planks.

A key aim for my research in the collections is to document these stories, things, and archives and make them more easily accessible, especially to Pasifika cultural practitioners. In the short term, this will be achieved by developing a publicly accessible map showing the geographic spread of the collections. This way, community members can easily search for their cultural materials by exploring the map. Each map point will link back to the NMNH online catalogue. This spatial resource will be accompanied by a database of published canoe resources, arranged by location in the Pacific. It is my hope that this work will support the ongoing work of revitalizing canoe carving, building, and voyaging by connecting communities with historical resources.