Image

The Artist, His Sculptures and his African Collection at the Smithsonian

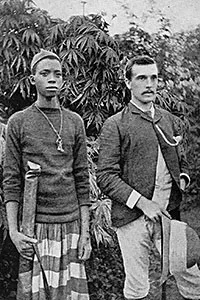

Born in London in 1863, Herbert Ward left home at the age of 15 and began his world travels first to New Zealand and Australia, later to Borneo. In 1884 at the age of 21 he set out for the Congo.

Between 1884 and 1888 Ward supported himself by working for various trading companies managing the transport of goods and supplies to and from European posts along the length of the Congo River. In 1888 he joined Henry Morton Stanley's Emin Pasha Relief Expedition serving the expedition in a similar capacity.

Following his return from Africa in 1889, Ward began a career as a writer and a popular lecturer about his Congo experiences. His lecture tours took him around the British Isles and to the United States. Upon his return from America he turned his attention to the fine arts.

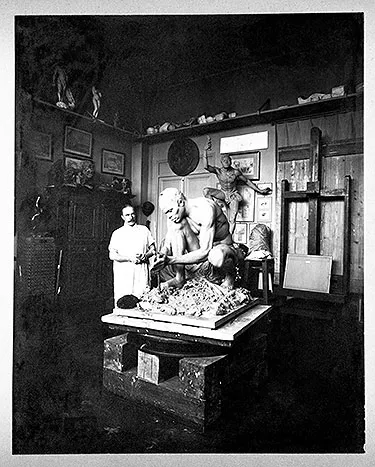

In 1893 Ward began formal studies in painting and sculpture in London and in Paris. In 1902 Ward moved permanently to Paris. He found that Paris provided him with an easier access to African and Caribbean models for his sculptures; the French had excellent foundries for bronze casting; and he enjoyed a greater acceptance of his Congolese subjects by the French art academy and the public.

Ward's sculptural style fit broadly within the British “New Sculpture Movement”. This group of British sculptors rejected the rigid neoclassicism of the previous generations and embraced a greater naturalism in their depiction of the human figure. They often depicted bodies in motion and the emotional states of their subjects.

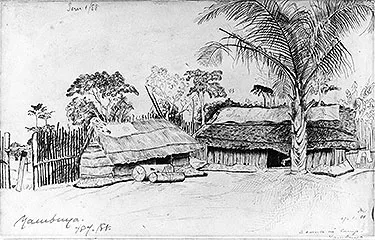

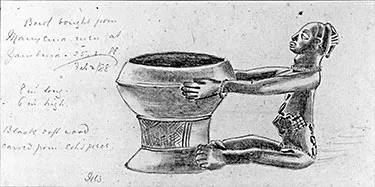

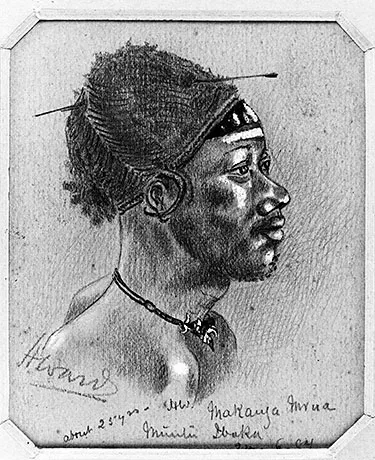

Ward used photographs and sketches, as well as objects from his Congo collection, as resources and inspiration for Congo vignettes. During his years in the Congo, Ward had taken photographs and filled sketchbooks with drawings of landscapes, people, and objects that he collected.

His careful attention to the details of hairstyles, facial and body scarification, ornament, and clothing and his references to Congo objects from his collection suggest a certain degree of ethnographic truth. However, Ward always insisted that his works were first and foremost art not scientific illustrations. He stated that his intention when creating his sculptures was to convey “the spirit of Africa in the broad sense.”

Ward's singular focus on Congolese subjects found a ready audience in France where a number of French sculptors regularly depicted African and Asian subjects in their works. His work fit broadly into the category of ethnographic sculptures, popular from the mid-19th century onward.

Ward was clearly a man of his time and his 1902 bronze, Sleeping Africa, seems to support the then popular theory that the development of African cultures had been physically and culturally retarded. This theory granted positional superiority to Western culture and it served as a moral justification for the European colonization of the African continent. The allegorical figure of Africa is depicted asleep on the map of the continent. The implication here is that colonialism will awaken the continent to his true potential.

A decade later, however, Ward had begun to question the excesses of the colonial experiment in the Congo which were then coming to light in the press. In his last sculpture, Distress or The Tragedy of the Congo, he represented the male figure in the classical posture of mourning.

Ward was a member of the Royal Society of British Sculptors. The regular acceptance of his works in exhibitions in Great Britain and France where he was awarded medals and the acquisition of his sculptures by art museums in Great Britain, France and South Africa attest to the generally high regard that his work enjoyed during his lifetime.

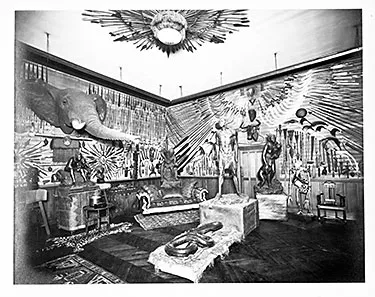

Around 1906 Ward installed his Congo collection on the upper floor of his Paris studio. In this private museum, Ward carefully and painstakingly designed the installation of objects in order to maximize the display’s aesthetic effect and to serve as a foil for his bronze sculptures of Congo.

His Congo collection numbered in the thousands. Although he had collected a large number of objects while working in the Congo, he continued to add to this collection while he lived in Europe. His collection included over a thousand weapons, and many textiles, carved figures, musical instruments, and personal ornaments

During World War I Ward served as a Lieutenant in No. 3 Convoy of the British Ambulance Committee where he distinguished himself. His exertions weakened his health and he died in 1919. In 1921, his widow, Sarita Ward, donated his collection along with his bronze sculptures depicting vignettes of Congo life to the Smithsonian. The curators designed the exhibition in Washington to capture some of the drama that Ward had achieved in his Paris display. They hung curtains over the windows to recreate the somber atmosphere of Ward's installation, which they described as evocative of the “jungle.” They mounted antelope and elephant trophy heads on the walls, surrounded by African weapons arranged in decorative patterns. Even so, the museum's installations were noticeably more restrained than the originals in Paris.

But, the curators also asserted the museum's scientific voice into the display. The Congo objects and the zoological specimens were organized in cases by type or function in line with the anthropological thinking of the day

The cases were displayed around the perimeter of the gallery and the displays included educational labels. The bronzes, rather than being fully integrated with the African objects as they had been in Paris, were all positioned in the central open space within the gallery. This exhibition, with minor revisions, remained on view until 1961.

Browse the collections records of objects from the Ward Collection at the Smithsonian. The Ward African Collection was donated to the Smithsonian in 1921 by Ward's widow, Sarita Ward.

Search the Smithsonian Ward Collection Online

The Herbert Ward collection can be viewed at the Museum Support Center in Suitland, Maryland. Appointments are available Monday through Friday, 9 am to 4:30 pm, excluding federal holidays. To request an appointment, please visit the Anthropology Department webpage